Subscribe to the Interacoustics Academy newsletter for updates and priority access to online events

Training in Functional Assessment and Rehab

-

Course: Advances in Vestibular Rehabilitation

-

Otolith Testing: Subjective Visual Vertical

-

The Benefits of Adding Functional Vestibular Assessments to Your Clinic

-

Otolith Testing in VNG

-

Diagnostic and Functional Evaluations of Vestibular Deficits in the Concussed Patient

-

Course: Objectifying the functional assessment of the dizzy patient

-

How to perform Dynamic Visual Acuity testing

-

Beyond bedside testing: Objective functional assessments of the Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex (VOR)

-

Gaze Stabilization Test in a case of concussion

-

Dynamic Visual Acuity (DVA) Test

-

The role of virtual reality in vestibular rehabilitation

-

Vestibular rehabilitation for concussion: A case study

-

Virtualis clinical education - Part 2

-

Virtualis clinical education - Part 1

-

Optimizing your functional balance assessment

-

Optimizing your vestibular rehabilitation programs

-

Motor Control Test (MCT)

-

Sensory Organization Test (SOT)

-

Rehabilitación vestibular: fundamentos para el abordaje integral de la persona con vértigo, mareo y desequilibrio

-

Evaluación y rehabilitación vestibular en la infancia

-

Computerized Dynamic Posturography (CDP): An Introduction

-

Limits of Stability (LOS)

-

Adaptation Test (ADT)

-

Clinical Test of Sensory Interaction on Balance (CTSIB)

-

Getting started: Functional Vision Head Impulse Test

-

Modified Clinical Test of Sensory Integration on Balance CTSIB (mCTSIB)

-

Persistent Postural Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD) Unpacked: A Modern Approach to Chronic Dizziness

-

From Diagnosis to Discharge: Utilizing the DATA model for comprehensive care of the dizzy patient

Functional Vision Head Impulse Test (fvHIT™)

Description

Table of contents

- Assessing the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR)

- What is the fvHIT?

- DVA vs GST vs fvHIT

- How to perform the fvHIT

- Interpreting fvHIT results

- Using fvHIT data in the management of the patient

Assessing the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR)

We have been studying the VOR for more than a hundred years, dating all the way back to the discovery by Robert Bárány of irrigation of the ear to stimulate the VOR through caloric testing, which was then joined by rotational chair testing, and then more recently, through the clinical use of video head impulse testing.

Bedside examination of the VOR using brisk impulsive movements was first described as clinical head impulse testing. Halmagyi and Curthoys described this in the late 1980s, looking at eye movement behavior relative to impulsive head movements [1]. This then developed through the technological advancement of lightweight goggles and cameras into what has now been used for over 10 years in clinic, the video head impulse test (vHIT).

The vHIT measures the physiological function (eye movement behavior) of the VOR at higher frequencies. This is complementary to what we consider as our lower-frequency VOR assessments through caloric and rotational chair testing.

However, despite these assessments examining the physiological reflex of the VOR, they do not provide any indication of the functional status of the VOR. To assess if the VOR is efficient enough to provide visual acuity, tests such as dynamic visual acuity (DVA) or gaze stabilization (GST) are required, as they assess the functional VOR whilst the head is moving in a predictable and sinusoidal motion, such as horizontally or vertically.

The patient’s task is to identify and call out to the clinician which direction a U-shaped optotype is pointing at during the head movement. This is then scored as either a correct or incorrect response.

A recent technological advancement within functional VOR assessments is the Functional Vision Head Impulse Test (fvHIT™), which we will dive into now.

What is the fvHIT?

The fvHIT, also known as the Functional Head Impulse Test (fHIT), is a functional VOR assessment that assesses a patient’s ability to maintain visual acuity during unexpected head impulses which are directed in the planes of the paired semicircular canals.

Like DVA and GST testing, the patient will see an optotype displayed in front of them, but at the peak of the head impulse movement, which is performed passively by the clinician. The patient’s task is to identify which direction the U-shaped optotype is orientated during the head impulse and is scored as either a correct or incorrect response.

The fvHIT looks at visual acuity during the accelerative element of the random head impulse. What that tells us is not only does the reflex work correctly, so physiologically which we measure through the vHIT, but also is it working functionally? So, during those head movements, can our patient use that physiological VOR to see clearly?

That is important to assess, as previous studies [2] have shown poor correlation between the physiological reflex measurement and reported symptoms by patients. This means a patient could have what are considered as normal physiological VOR responses in the vHIT but experience visual-acuity difficulties in their activities of daily living. These are most often reported by patients as symptoms or complaints that head movements make them feel dizzy.

DVA vs GST vs fvHIT

With the addition of the fvHIT in our functional VOR assessment toolbox, we now have three functional VOR assessments to choose between: DVA, GST, and fvHIT. When deciding which test to perform and in which order, there are a few considerations worth noting.

1. Test speed

One way to look at the difficulty of these tests is how fast the head is moving. If we were to organize these tests from slow to fast, we would organize them in this order:

- DVA (75 to 100 degrees per second)

- GST (up to 200 degrees per second)

- fvHIT (1000 to 7000 degrees per second squared)

When you have a patient coming into your clinic and you are trying to decide which tests you will be doing, it is worth considering starting off with the DVA test. If your patient can perform that well, then you could move on to a more difficult test of the functional VOR.

This is similar to the approach we might adopt in a balance assessment (such as the CTSIB), where we would usually start with an easy condition. For example, start off with the patient standing on a flat, firm surface with their eyes open. If the patient did well in that condition, then you would make it more difficult by having them close their eyes, stand on a dynamic surface, provide sway-referenced vision, or a combination of the before-mentioned.

With functional VOR assessments, by making it more difficult for the patient, we are continuing to test until we reach the point at which their VOR system breaks down.

2. Planes of motion tested

When compared to DVA and GST testing, the fvHIT as a functional test of the VOR more closely aligns with the physiological assessment of the VOR with vHIT, as it also assesses the patient’s function in planes of head motion tested (horizontal and vertical in the vestibular semicircular canal planes).

3. Cognitive load

Another thing that you may want to think about is the cognitive load of these functional VOR tasks (Table 1). What we mean by the term ‘cognitive load’, especially when we apply this to the fvHIT assessment, is that the patient must recognize the optotype and correctly identify the direction it is orientated during unpredictable and rapid head impulses. This is a more complex and detailed assessment of the brain’s VOR system than just measuring the correction of eye position as we do in vHIT.

| Assessment | Task | Head movement predictability | Cognitive load |

| DVA | Identify direction of optotype | High | Medium |

| GST | Identify direction of optotype | High | Medium |

| fvHIT | Identify direction of optotype | Low | High |

Table 1: Cognitive load of DVA, GST, and fvHIT.

Following the same logic as we have discussed for test speed, you might opt to start off with DVA and/or GST and follow up with fvHIT. For example, Amy Alexander, Physical Therapist at Banner Sports Medicine and Concussion Specialists, uses fvHIT as a follow up to her GST testing:

“I use fvHIT as part of my GST battery, where it has been a useful tool in identifying a deficit when GST testing is both athlete appropriate and adequately symmetrical.”

4. Clinical judgement

In general, the more assessments you have in your test battery, the more information you have to personalize your patient’s rehabilitation plan to ensure they get better faster. The choice of which test(s) to do depends on your clinical judgment and the patient’s reported symptoms. Depending on what they report, you may choose a different test strategy and/or sequence to identify where that patient is experiencing dysfunction or difficulty.

How to perform the fvHIT

Now we will look at how we can conduct the fvHIT.

Required equipment

The fvHIT is operated through the VisualEyes™ software, and is a part of two VORTEQ™ bundles:

- VORTEQ Assessments (add-on to VisualEyes including VNG goggle)

- VORTEQ Functional Assessments (standalone solution without VNG goggle)

In terms of hardware, part of this assessment is the patient calling out the direction of the optotype, and the clinician needs to mark that as being correct or incorrect.

The clinician will use the included remote control, computer touch screen, or computer keyboard to mark the direction of the optotype (the software then automatically scores that input as correct or incorrect).

A separate, smaller monitor is recommended to perform the functional VOR assessments, different from your large screen used for oculomotor testing. The size of the screen determines the required distance between the screen and the patient. For fvHIT testing, a typical computer monitor is recommended for a minimal footprint (Figure 1).

Read more: How to set up and troubleshoot monitors for oculomotor and optotype tests

The measurement of the velocity and acceleration of the head impulses is done by the included headband and VORTEQ sensor (Figure 2). Once you have placed this onto the patient’s head, you are ready to start testing.

Static visual acuity assessment

Now, we are ready for the first part of the test, which is the static visual acuity assessment. With the patient set at the correct distance for the screen or monitor that you are using, we will instruct them to keep their head still and call out the direction of the optotype.

The clinician will use the remote control, computer touch screen, or computer keyboard to mark the direction of the optotype correctly or incorrectly called out by the patient. The test will run until we get a repeatable static visual acuity assessment, and that is important because we are going to use that to determine the optotype size when we test further in the fvHIT.

If the patient responds with the correct direction of the optotype, the optotype will get smaller (and vice versa larger if they respond incorrectly). The goal is to determine the patient’s threshold (two correct answers at the same optotype size).

Static visual acuity testing should be performed with the patient’s best visual condition. So, if the patient wears glasses or contacts, they should be wearing them for the static visual acuity test and all subsequent tests.

Visual processing time

The next assessment we perform is to assess the patient’s visual processing time. This is an important assessment to conduct before we start moving the patient's head dynamically, and the way we conduct it is very similar to what we have just completed with the static visual acuity assessment.

We display the optotype, ask the patient to call out the direction of the optotype, and mark it correct or incorrect. What is different here is the software will vary the presentation time of the optotype.

From this assessment, we can calculate how quickly the patient can reliably identify that optotype. Now, that is very important because some patients will have different visual processing times, and we need to take that into account before we start moving the head dynamically.

It is super important to identify patients who may have longer visual processing times, because if we start to move the head, we want to be confident that the results we're gathering are related to the functional VOR and not because of a delayed or slow visual processing time. Satisfactory visual processing time is between 30 milliseconds and 70 milliseconds.

fvHIT

After the static visual acuity and visual processing time assessments, we are ready to perform the fvHIT. The technical test procedure for fvHIT should be identical to vHIT testing with randomized quick head impulses. Note: In fvHIT, you will be varying both the head acceleration and direction.

As with vHIT, in fvHIT we firmly hold the patient’s head (avoiding the headband) and thrust the head in appropriate direction and canal plane. It is recommended to get at least 30 impulses in each direction, at a variety of head speeds/accelerations.

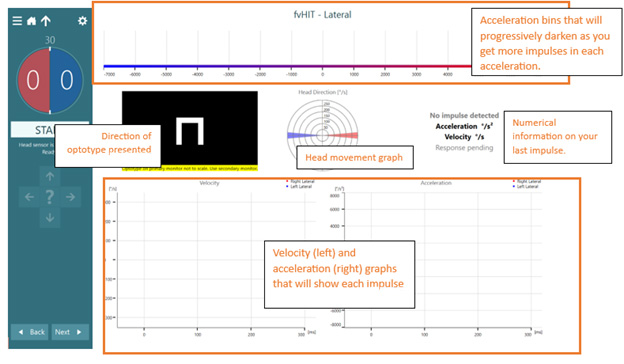

The test screen is composed of a variety of indicators to assist you during testing.

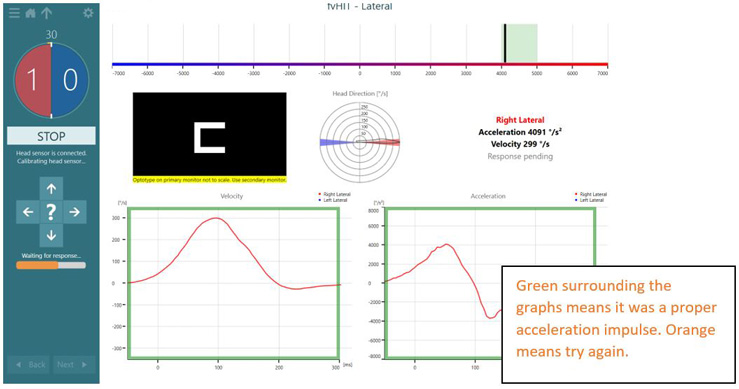

After one head impulse, the screen will look like this:

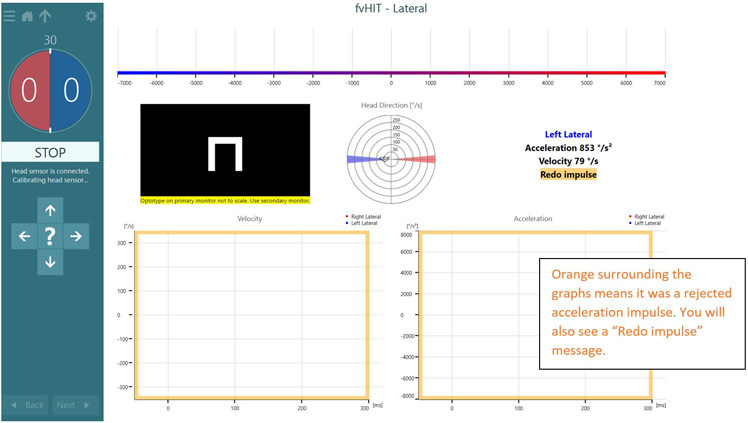

If the velocity of the head movement is too slow or too fast, you will see an orange bar surrounding the head impulse graphs and see the “Redo impulse” message.

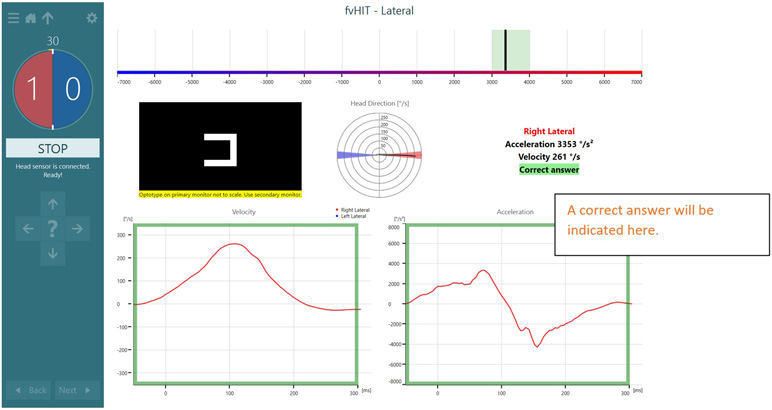

After each impulse, you will have your patient verbally respond with which direction the U-shaped optotype was facing. You will be able to see if the answer was correct or incorrect.

As you continue to increase the number of head impulses, you will see the counter on the left increase in number, and you will also see the acceleration bins get progressively darker. As the bins get darker, you should focus on other acceleration bins.

Note: Unlike vHIT, the test will not automatically stop when you have collected 30 in each direction. You can stop the test at any time. 30 is the recommended number of impulses as it allows for approximately 5 impulses per acceleration bin. In certain populations (pediatrics, concussion, and cervical injury), 30 impulses may be difficult to achieve.

Interpreting fvHIT results

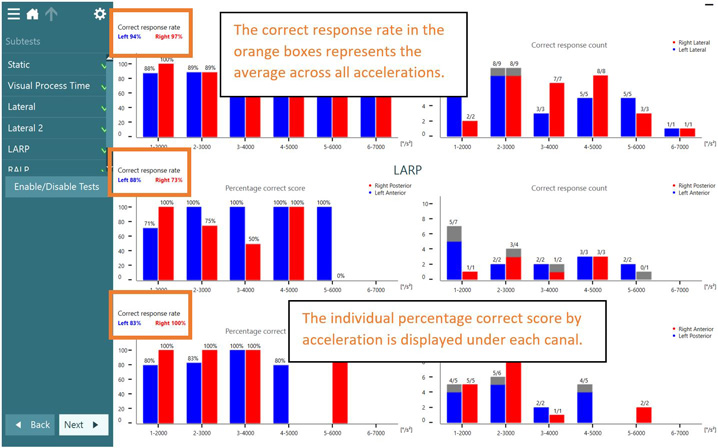

After completion of all horizontal and vertical planes tested, you will see this summary (Figure 8).

You will spend most of your fvHIT interpretation time on the summary screen. The summary screen has three main components that we are going to discuss in more detail:

- Average correct response rate

- Percentage correct score

- Correct response count

These three items are going to be your focus of attention when you collect data on a patient because they will help you determine the appropriate steps for how to get that patient feeling better and improving their symptoms.

Average correct response rate

We know the task for the patient in this test is to tell us which direction the open part of the U-shaped optotype is facing. The average correct response rate is a percentage score that tells us how many times the patient got something right versus how many times they got something wrong across all acceleration bins.

All those impulses and all the answers are collected to give us this average correct response rate. Ultimately, this calculates all the correct impulses throughout all the head accelerations from all the impulses collected.

This number gives a very quick idea of how the patient performed for rightward versus leftward head impulses. It considers all the data, so we are not looking at acceleration-specific data. Ultimately, the average correct response rate answers a good first question: Is there an asymmetry for rightward head impulses versus leftward?

When you look at the research for the Functional Head Impulse Test, you are going to notice that this is the number that is most often reported. Research tends to focus on this average correct response rate to determine how specific populations do in this test. So, if you investigate any of the studies that are already out there, this is probably the number you are looking at.

Most of the research that has been published shows that normal individuals perform about 88% and above for their average correct response rate [3]. There are some caveats with that number because every research study so far has been performed a little bit differently. They are focusing on different acceleration bins or head speeds/accelerations, so we must take all that reported normative data with a bit of a grain of salt because it is not performed in the same capacity as testing with VisualEyes fvHIT may be done.

In addition, the average correct response rates previously reported have a large range of variability. Whilst most people do about 88% and above, the range for normal can be plus or minus 10%. This means that anywhere from 78 to 98% can be considered normal. While we have looked at specific age populations in the research [4], there still needs to be a lot more research done on how certain ages are expected to perform with this test and what is realistic for how we expect a patient to perform at different head accelerations.

Percentage correct score

On the left side of the screen in Figure 8 are your percentage correct scores for the lateral (horizontal), LARP, and RALP (vertical) canal planes. The percentage correct score looks at how many are recorded as right and how many are wrong. The red bars represent right lateral head movements, and the blue bars represent left lateral head movements.

The Y-axis looks at the percentage correct. If a patient performs perfectly, you are going to see 100% in every acceleration bin. The X-axis shows our acceleration bins, and this represents the acceleration of head movement. We look at accelerations between 1000 to 7000 degrees per second squared.

Looking at these graphs allows you to answer the following questions:

- Does the patient's performance get worse as the head acceleration increases?

- Or do you see that performance is equivalent across all the acceleration bins?

Answering these questions from this graph is very helpful information for you to know as you prepare your patient's next steps for rehabilitation.

Correct response count

The last thing on the summary screen is the correct response count. You will notice that red represents the right lateral, and blue represents the left lateral. The X-axis is still the acceleration bins, but now the Y-axis is the total number of impulses performed.

Depending on the acceleration bin that you are looking at, there may be a different number of impulses collected. As you are getting comfortable doing this test, you will notice that technically as a clinician, sometimes it is hard to vary the acceleration of the patient’s head. This may especially be the case if you are very familiar with performing the vHIT, where you are looking for similar acceleration, and are varying the velocity of head movement in each head impulse.

It can be a challenge to start varying your technique to produce the head acceleration for patients. As you get started with this test, you may have a high number of impulses in those mid-ranges (all in degrees per second squared):

- 2000

- 3000

- 4000

- 5000

But, as described above in how to perform the fvHIT, you receive live feedback during testing, which can give you a visual indicator of which acceleration bins to target to complete the assessment.

To collect valid results, aim to perform at least three, ideally five impulses per acceleration bin to be confident with the data. Low numbers of impulses in an individual acceleration bin could distort the data, which is why we recommend between 3 and 5 impulses.

Once you have collected enough data in each acceleration bin, the correct response count also helps to answer the following questions:

- Does the patient's performance get worse as the head acceleration increases?

- Or do you see that performance is equivalent across all the acceleration bins?

Using fvHIT data in the management of the patient

With the fvHIT completed, the next question we might have is how do we take the results and use them to create customized training for our patients? Watch the video below (or read the transcript) with Cassie Anderson, PT, DPT to find out.

In summary, fvHIT results can be helpful in:

- Validating a patient’s head-movement-related dizziness or other symptoms.

- Creating a baseline for beginning rehabilitation.

- Tracking progress over time with selected intervention.

- Determining when the patient’s VOR performance is back to normal and thus when the patient can be discharged from rehabilitation.

Click here to read the full transcript

First, let's make sure that we all understand we want to make sure we use all our functional assessment results when assessing the patient, VOR function, sensory integration and postural control. But if someone has VOR deficits, we really want to make sure we're starting with VOR training because if someone has visual blurring when they're moving their head, it really will negatively impact their overall balance.

DVA and GST

First, look at the DVA and GST. This gives good information of how the patient is moving their head in specific directions, leftwards, rightwards, up and down, these are kind of what we expect of daily functional head movements. From the DVA, the GST, I'll look at the peak head velocity. That's the number that lets me know where I should start the VORx1 training.

fvHIT

After GST I'll look at the fvHIT. This gives me great information about those rapid head movements, as a PT, I think, about those safety movements related to head movements. If someone has to quickly turn their head and be able to look at something, I want to make sure they're not dizzy or off balance doing these quick movements.

For the fvHIT, I'll look at peak acceleration across those acceleration bins and understand which plane of the patient’s head movements are affected, as well as if there is a speed component that I want to make sure I'm incorporating in my training.

Home exercise programs

That brings us on to training. The next step, we know we can't do everything in the clinic; we've got to get that patient to be doing these very consistently at home, so we move into those home exercise programs.

There are four main types of gaze stabilization or VOR training exercises:

- VORx1

- VORx2

- Head impulse training

- VOR with convergence

VORx1 and VORx2

Most clinicians are probably familiar with VORx1 and VORx2. They're well supported in the published literature; they've been around for a long time. We know if our patients perform those consistently and appropriately, it'll reduce their visual blurring symptoms, and their overall function will improve.

The other two exercises we might be a little less familiar with.

Head impulse training

We have the head impulse type training where the patient is looking at an object placed on the wall and moving their head quickly to one side. This has been supported in recent evidence or recent literature that if you perform these, it actually can help improve those rapid head speeds and reduce the symptoms.

VOR with convergence

The last one is the VOR with convergence. This is having a patient perform those VOR exercises at a near target, so about 15 centimeters away from the bridge of their nose. Research has really supported these as well, and we can help improve the passive VOR gain by improving eye position and visual acuity with these exercises.

By using clinical practice guidelines, we know that if a patient performs these VOR training exercises from anywhere from a total of 12 to 20 minutes a day for over two to seven weeks depending on the type of vestibular loss and the chronicity, that their symptoms will improve and their function will also improve.

In-clinic training

I have my patients who come back after performing their VOR training exercises and they're a little upset, right? They often say: "Those are boring. They make me a little dizzy. I don't want to do those in clinic." I always try to encourage the patient, "You have to perform these at home, they're well supported in research, but when you come into clinic, let's do something a little bit more optimized. Let's work on the symptoms that you're actually reporting in your daily activities."

I really like using technology, specifically virtual reality. I can immerse the patient into these daily activities, have them perform specific head movements based on the fvHIT results, and as well set the speed.

Let's look at a quick virtual reality exercise where this patient is immersed in this environment. Let's consider a patient that on the fvHIT they had deficits in the LARP vertical plane. I could set the head movements specifically in the LARP plane and I could set that speed at where that patient needs to start that exercise.

Then as the patient performs the exercise, I'm getting good objective feedback on the computer screen so I know when I can increase the speed a little bit more. Can I push the patient a little bit harder in clinic to make sure that they're really getting that customized and optimized rehab?

When to discharge patients

I always want to make sure that clinicians understand to redo those functional assessments that have been completed previously, like the fvHIT, to understand, has my patient improved? Can I modify the exercises? Can I make things a little bit harder or do I need to make things a little bit easier, so they continue to progress with rehab?

Then I always pair the objective data from these functional assessments with their subjective reports. How are they feeling when they're at home? Do they still have dizziness picking things up off the floor? Do they still have dizziness when they're going to the grocery store?

Once they're subjectively feeling better as well as those objective results improve, then that tells me the patient's ready for discharge.

Conclusion

The fvHIT is a cutting-edge tool for diagnosing functional VOR deficits both at quick head movements, but also in the planes of the paired semicircular canals of the vestibular system. This is important in patients reporting dizziness associated with head movement and you can use the results to guide tailored and personalized vestibular rehabilitation.

As adoption grows, fvHIT will become a core component of the assessment of functional deficits in patients with symptoms of visual disruption with head movement, complementing vHIT, DVA, and GST testing.

fvHIT is also an important component of a dizzy patient’s care journey, known as DATA (Diagnose, Assess, Train, Assess). Sitting in Assess, fvHIT allows clinicians to measure the patient’s functional performance to determine how a patient performs with their diagnosis (as we know two patients with the same diagnosis can have very different symptoms and performance).

We also revisit the fvHIT after training to ensure the intervention was successful and appropriate for the patient’s needs.

Related courses

References

[1] Halmagyi, G. M., & Curthoys, I. S. (1988). A clinical sign of canal paresis. Archives of neurology, 45(7), 737–739.

[2] Balayeva, F., Kirazlı, G., & Celebisoy, N. (2023). Vestibular test results in patients with vestibular migraine and Meniere's Disease. Acta oto-laryngologica, 143(6), 471–475.

[3] Cengiz, D. U., Erbek, H. S., Çolak, S. C., Kurtcu, B., Demirel Birişik, S., Karababa, E., Kuşman, B., Özdemir, E. A., Işık, M., & Demir, İ. (2023). Evaluation of vestibulo-ocular reflex with functional head impulse test in healthy individuals: normative values. Frontiers in neurology, 14, 1300651.

[4] Goetz, C., Fuemmeler, E., Petrak, M., & D’Silva, L. J. (2025). Functional Vision Head Impulse Test: A Functional Measure of the Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex. Paper presented at the APTA Combined Sections Meeting (CSM), Houston, TX.

Presenter

Get priority access to training

Sign up to the Interacoustics Academy newsletter to be the first to hear about our latest updates and get priority access to our online events.

By signing up, I accept to receive newsletter e-mails from Interacoustics. I can withdraw my consent at any time by using the ‘unsubscribe’-function included in each e-mail.

Click here and read our privacy notice, if you want to know more about how we treat and protect your personal data.