Subscribe to the Interacoustics Academy newsletter for updates and priority access to online events

Training in Corticals (ALR P300 MMN)

-

P300 Evoked Potential: A Deep Dive (1/2)

-

P300 Evoked Potential: A Deep Dive (2/2)

-

ASSR: 95% or 99% Statistical Confidence?

-

Cortical Evaluations Without a Loudspeaker

-

Why use Jumper Cables with the EPA4 Cable Collector?

-

Mismatch Negativity (MMN) Case Study

-

A Deep Dive into Mismatch Negativity (MMN)

-

Auditory Late Response (ALR) in Adults

-

Validation in pediatric hearing aids

-

Which stimuli should be used for aided cortical testing?

-

Getting started: Aided cortical testing

-

Beyond the Basics: Aided cortical testing

-

Aided cortical testing – considerations when testing cochlear implant patients

-

How to interpret aided cortical waveforms

-

How to develop a testing strategy for aided cortical testing

-

What are the options for hearing aid management following aided cortical testing?

-

Aided cortical testing - considerations for unilateral and asymmetrical hearing losses

-

Aided cortical testing – considerations for patients with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder

-

Perfecting your test technique: Aided cortical testing

-

Aided cortical testing - the clinician's perspective

-

Aided cortical testing - tips and tricks

-

Testing a 4 month old baby using the aided cortical test

-

Aided Cortical Testing in Action - Assessing Aided Benefit with CAEP

Aided Cortical Testing: A Complete Guide

Description

The aided cortical test can be likened to an evoked potentials method for performing a speech test. This guide will provide a complete introduction to aided cortical testing.

Table of contents

- What is aided cortical testing?

- Why should we do aided cortical testing?

- Who should we do aided cortical testing on?

- Which stimuli should be used for aided cortical testing?

- How to set up the equipment for the test

- How to use the Sound Field Analyzer

- Patient preparation

- Interpreting aided cortical waveforms

- Hearing aid management

- Complex testing scenarios

What is aided cortical testing?

To understand what aided cortical testing involves, it's helpful to firstly take a step back and consider what traditional cortical testing is and involves.

Categorizing auditory evoked potentials

When considering auditory evoked potentials, these can be categorized in several different ways.

We can consider the latency or timing of the evoked potential response and differentiate between different responses accordingly. Short latency responses include cochlear microphonics, electrocochleography, and the auditory brainstem response. The middle latency response occurs at a longer latency, and then we have the very longest of our evoked potential responses.

We can also consider or categorize evoked potential responses according to anatomical region.

The earliest of our responses are generated by the cochlea, auditory nerve, and the auditory brainstem. As we progress further along the auditory pathway, the longer latency responses such as the middle latency response is generated at the thalamus, and those longest of responses are generated by the cortical region, the furthest part of the pathway.

Cortical responses are typically seen as the P1-N1-P2 complex, which appears at around 100 to 300 milliseconds. There are a number of different names used for these tests, and many of these are interchangeable. Some of these tests are standard threshold or detection assessments, but we also have mismatch negativity (MMN) and P300 which look more at discrimination ability.

A standard threshold cortical assessment involves presenting tonal frequency-specific stimuli via insert earphones in order to establish threshold information with the goal of acquiring an audiogram. This is often preferable to ABR assessment as the patient must be awake rather than asleep, which is easier to achieve in adults and older children. Further advantage of cortical assessment over ABR is that it provides information regarding the full extent of the audiological pathway, beyond just the brainstem.

It is also now possible to perform aided cortical assessment, which involves presenting the stimuli via a loudspeaker instead of the insert earphone transducers. Whilst facing the loudspeaker, the patient has their hearing device or devices in-situ and switched on.

Because this is an aided test, speech sounds are used as the stimuli instead of tonal sounds. This is important because hearing aids are designed to listen to speech sounds. There can be variability in how hearing aids process tonal sounds. Standing waves can also become problematic in a free-field setting.

Ultimately, the goal of any form of aided testing is to know whether the patient is able to hear speech sounds properly with their device or devices in situ.

Aided cortical responses in adults

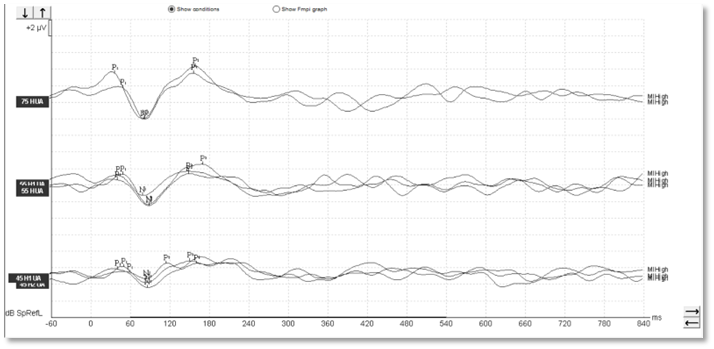

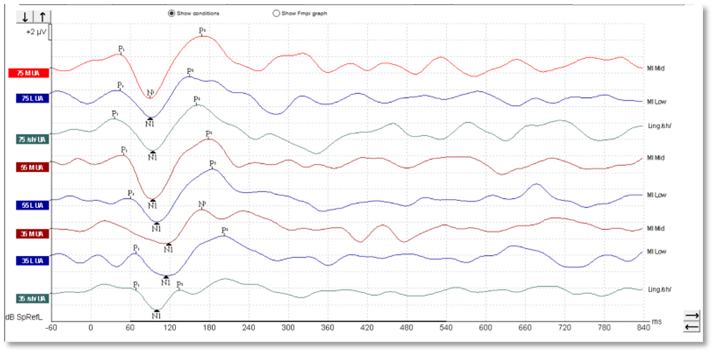

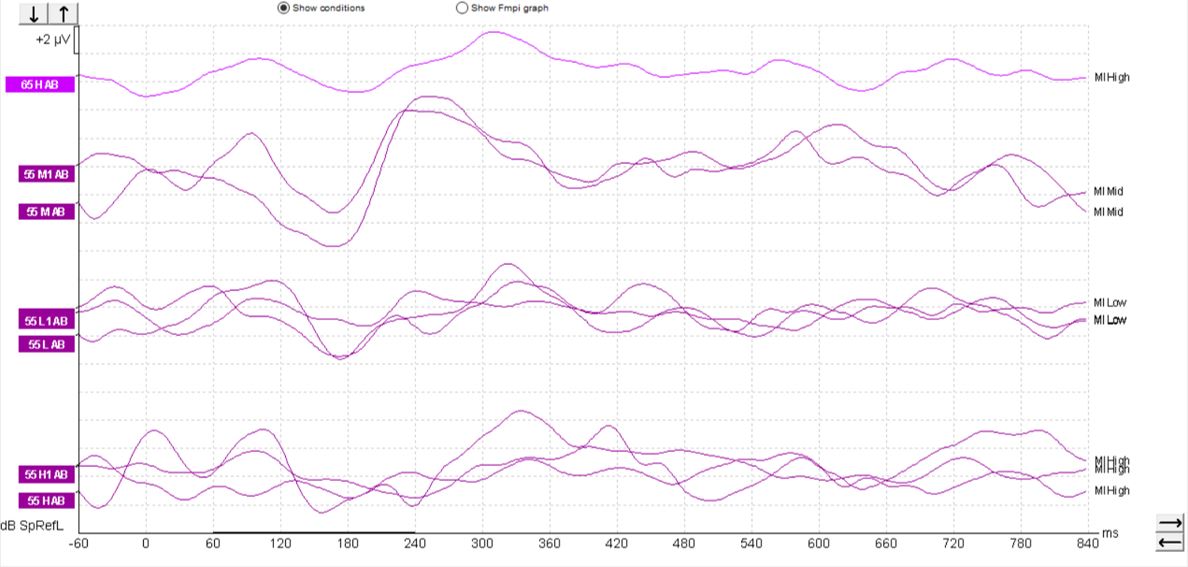

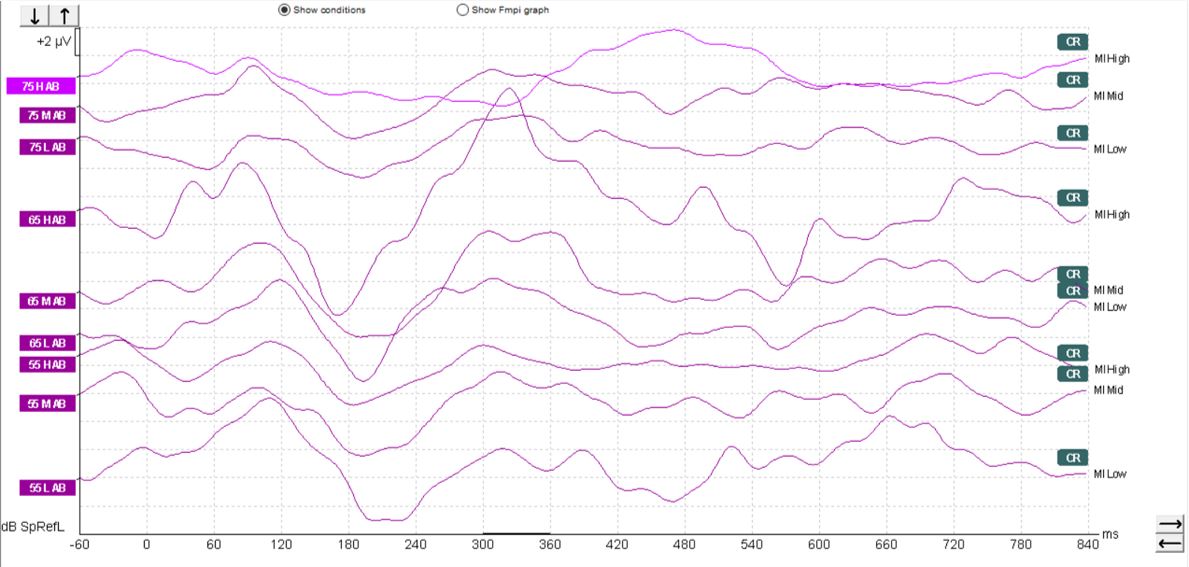

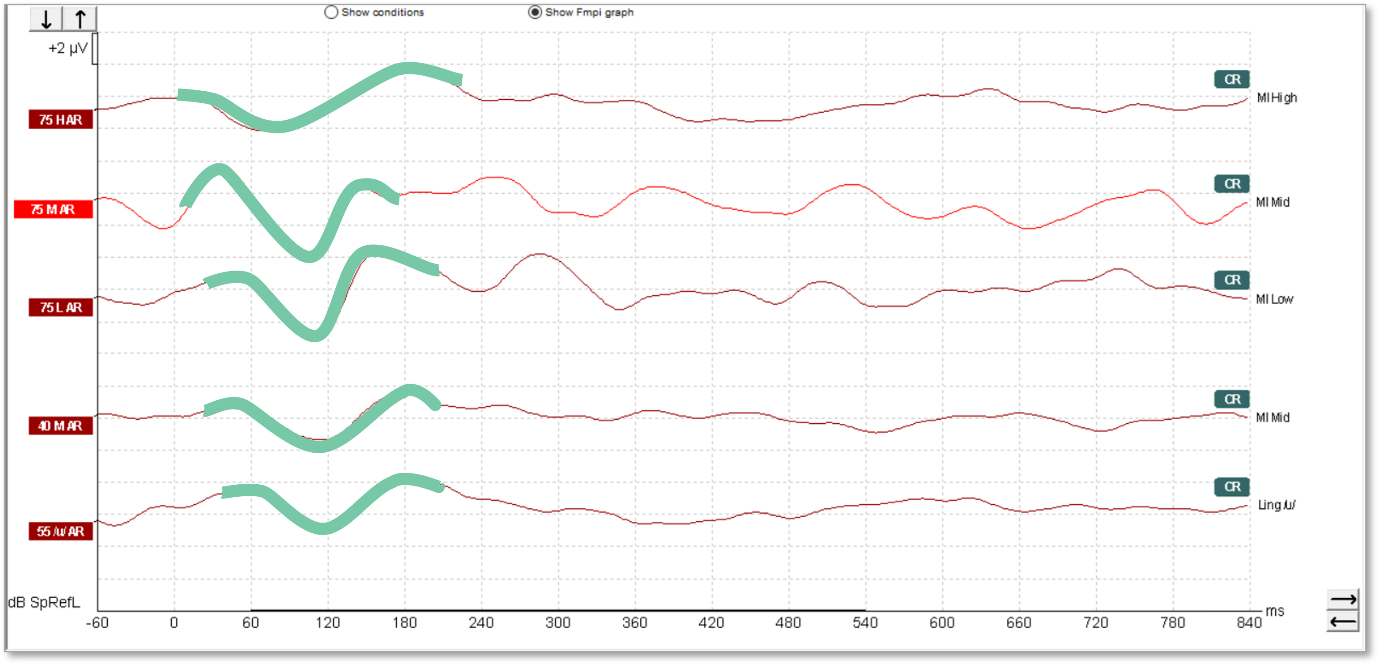

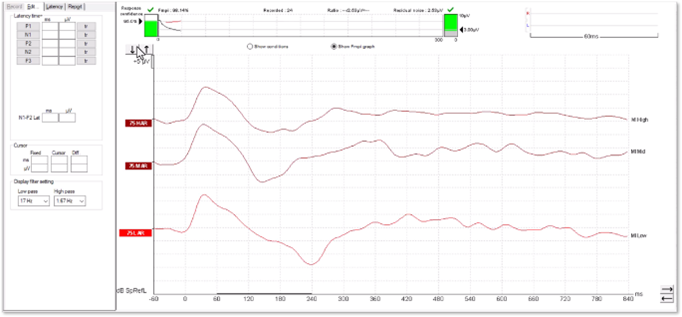

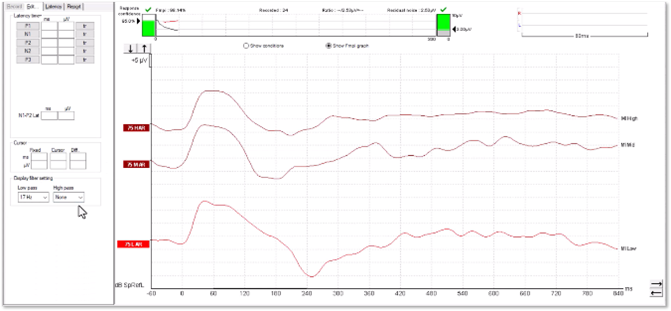

With aided cortical testing, or indeed any cortical testing, the waveform morphology in adults is generally quite clearly defined and repeatable and consistent across patients. In Figures 1-3, we can see a number of different waveforms, showing that traditional P1-N1-P2 complex.

Figure 1

Aided cortical responses in children

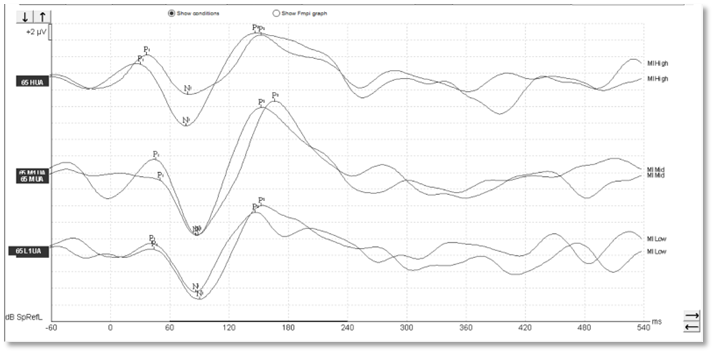

In children, it's a different matter. As you can see from the waveforms below (Figures 4-6), there is a much less clearly defined response morphology, and the literature shows that there is large variability in the response morphology between subjects. This is largely due to the immature cortex in this age group. The cortex does not fully mature until teenage years.

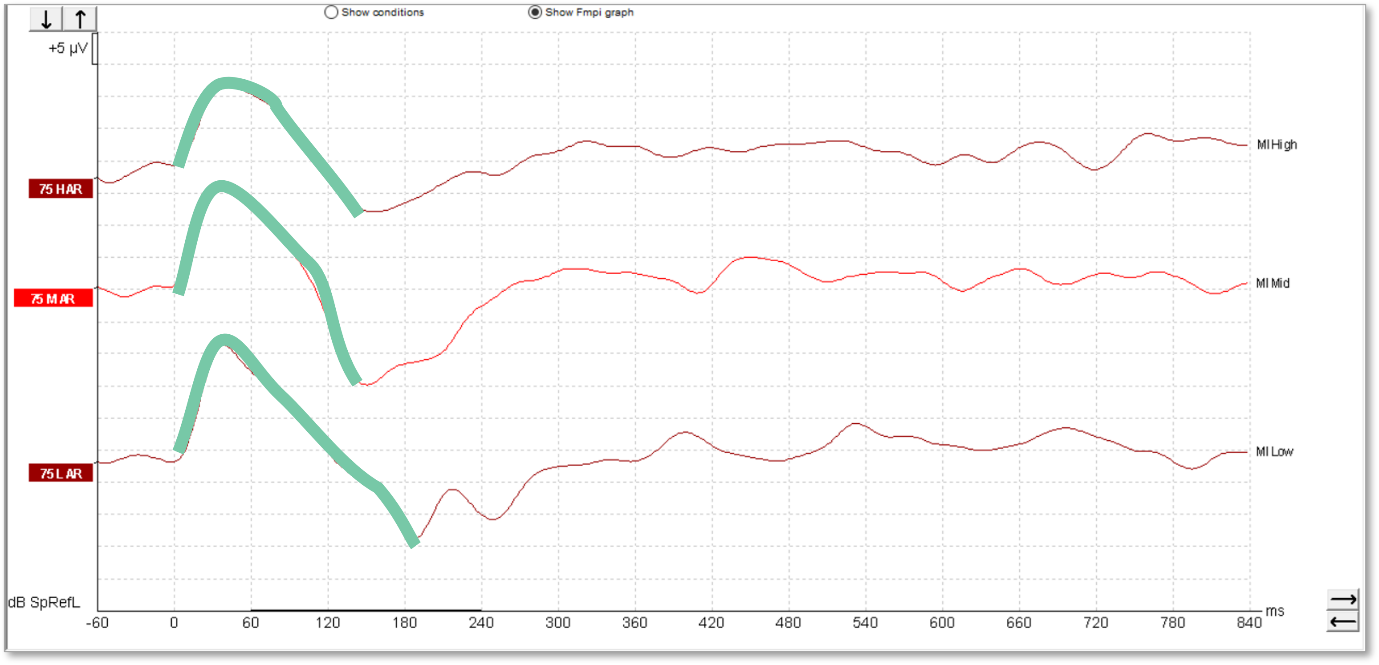

Aided cortical responses in cochlear-implant patients

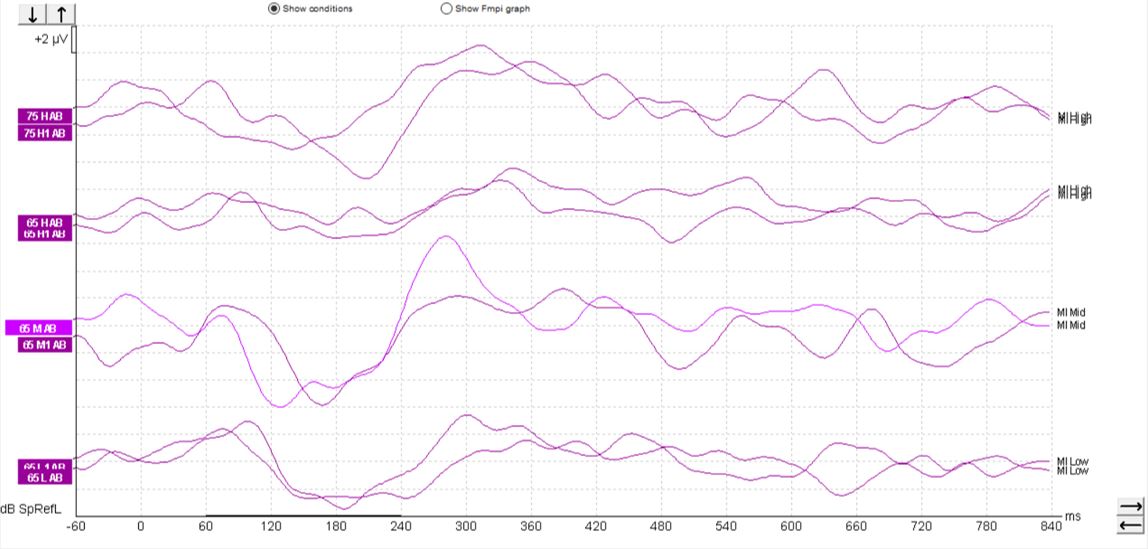

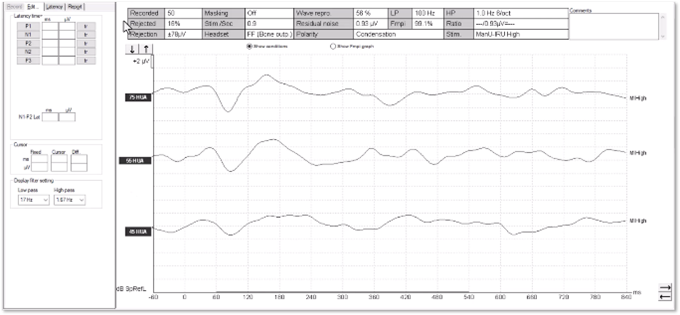

When testing patients with cochlear implants, a similar morphology can be seen, such as that shown in Figure 7 below.

However, sometimes it can be possible to record an artifact when testing patients with cochlear implants, so care must be taken when interpreting such responses. We can see artifacts in this set of recordings (Figure 8).

These artifacts can look quite similar to cortical responses. Key warning signs that an artifact is present is the slightly triangular or square shape present in the waveform. We can see the first positive inflection appears much earlier in latency than we would expect for a cortical response. Here it is just after 0 milliseconds. It is also likely to appear very quickly from the start of the recording.

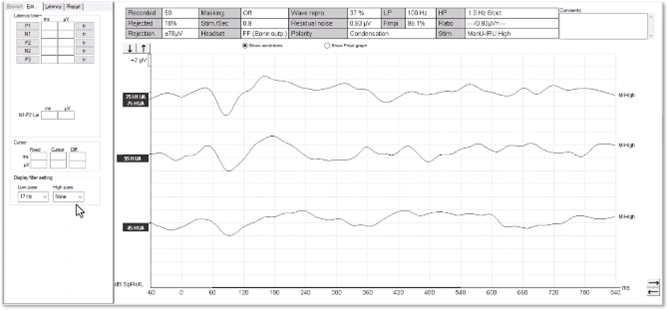

It is possible to examine any suspected artifacts by removing the display filter settings. When an artifact is present within the waveform, the peak of the artifact is likely to become flat and square-shaped upon removal of the display filter settings. A true cortical response would not modify in this way: When removing the high-pass filter setting, in particular for a non-artifactual response, there is likely to be little change to the shape of the positive inflections.

When testing patients with cochlear implants, it is important to explore these elements of the waveform to help distinguish between genuine responses and artifacts. Clinicians assessing patients with cochlear implants should proceed with caution when interpreting waveforms as the objective response detector may indicate the presence of a response when in fact the waveform contains an artifactual morphology.

Why should we do aided cortical testing?

So why should we be performing aided cortical testing? What benefit can it bring to the audiological test battery?

When it comes to fitting a hearing aid, there are many steps involved to ensure that the device is well-programmed. This includes performing accurate audiometry, speech testing, maybe speech-in-noise testing as well. Clinicians might perform audible contrast threshold (ACT™) testing. An appropriate device is selected for the patient, their audiogram and their needs. HIT box measurements are useful to help ensure the hearing aid is working properly. And the device should be verified using real ear measurements or RECD measurements.

But how do we know for sure if the device is actually doing its job properly? This is a question that differs for different people and different age groups.

For an older adult, it might be a matter of, does the device allow them to hear the television properly or to hear their grandchildren properly in the playground?

For someone in the workplace, it might be about whether the hearing device is working such that they can listen clearly in meetings or to presentations.

For children, it might be about whether they are able to hear the teacher in the classroom.

And for young infants, it's almost always about whether they can hear well enough to learn and develop their own speech and language.

This is why early intervention is so important. The child will only learn to speak as well as they can hear. So if they don't hear certain sounds, they will struggle to learn to speak themselves.

Outcome measures

To find out if a device is working as desired for that individual, it is possible to use what are called outcome measures. These are methods of measuring how good an outcome the patient is deriving from their device.

The clinician can ask the patient, using self-reporting measures, and get them to provide feedback about their personal experience of using the device in those situations where they need it to work well for them.

Validated questionnaires are also an option, and these exist for different age groups, crossing adults and children.

The input of other people in the patient’s life can also be valuable. For children, this might be their schoolteachers, asking how their school progress is going - are they keeping up with the rest of the class?

It is also possible to do direct speech testing with the patient, and speech-in-noise testing as well, with the hearing aids on to answer the question of: Does the patient hear more speech sounds with their devices on than they did without the devices?

But what if the patient can't do any of these outcome measures?

Maybe they're too young to self-report. Maybe they have additional disabilities or complex needs, such as a developmental delay or cognitive difficulties. Maybe they're too young for their parents or teachers to have any reliable reporting about their progress. This is where aided cortical testing becomes really valuable.

The aided cortical can be likened to an evoked potentials method for performing a speech test. If a cortical response is present to the speech sound delivered to the patient, then there is confidence that they can hear it. This can be done with or without their hearing devices in situ. It is then possible to make that comparison between aided and unaided performance.

Gap in infant hearing assessment

At the neonatal stage, the available audiological tests are limited to those which require no cooperation from the patient:

- ABR

- OAEs

- ASSR testing

- Tympanometry

These tests can easily be performed under natural sleep, however after approximately three months of age it becomes much more challenging to maintain sufficient natural sleep for the testing required.

Once a child has developed the trunk and neck control to be able to sit upright and perform a head turn, visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA) becomes possible. This typically occurs at around 7-9 months of age. VRA involves the child turning in response to a stimulus, upon which they are then rewarded with a visual reinforcer such as a toy or a video on the screen.

And it is at around two and a half to three years of age when a child can progress to a more cooperative task, such as play audiometry, where they perform a more conscious task in response to the heard stimulus.

Therefore, there is a gap between the ages of three to seven months where very limited testing options are available. ABR testing can be performed under sedation, however this carries risks and comes with more complicated practical consideration.

Frequently at this age, for those children who have been issued with hearing aids, the main clinical question is not about their underlying hearing levels, but rather whether and how well their hearing instruments are working for them. As a result, ABR testing is not suitable to answer this question.

Newborn hearing screening programs

At the neonatal stage, newborn hearing screening programs have been implemented in order to provide early intervention for children with hearing loss, and it is well known that early intervention leads to better outcomes for our patients. In many countries such as the US, England and Australia, newborn hearing screening programs work to a target of offering a screening test to 97% of babies within the first month of life.

Following newborn screening, the next step in the clinical pathway is to perform a diagnostic assessment of the child's hearing.

In England, there is a target that 97% of babies should be seen for diagnostics within four weeks of referring on their newborn screening test. The statistics for 2020-21 showed that this outcome was under target but largely influenced by the coronavirus pandemic.

In the US in 2021, 36.646 patients were seen for diagnostics following the newborn screen, and 4.252 were diagnosed with a permanent hearing loss by three months of age.

In Australia, there's a target that greater than 97% of children referred from the newborn screen should undergo diagnostic audiology assessment by three months of age.

Early intervention does not stop at the point of diagnostics. To ensure the best outcome, it is essential that amplification is provided where warranted, as soon as possible.

In Australia, hearing aid fitting should take place as early as possible, but no later than six months, with a target of over 85 % of children with bilateral permanent childhood hearing impairment to be fitted by six months of age.

In England, hearing aid fitting should be offered within four weeks of confirmation of a permanent childhood hearing impairment.

In the US, the target is to enroll patients in an early intervention program within six months of age. In 2021, this led to 2,750 babies being enrolled, many of whom will have received hearing aids, but this also includes those referred for family support, cochlear implants or medical intervention.

It is clear to see how newborn hearing screening has brought forward not only the diagnosis of hearing loss, but also the fitting of hearing aids to a much earlier point in time. Prior to these screening programs being in place, many hearing losses simply would not have been identified until much later in life when parental concerns or difficulties with speech and language development became apparent.

Aided VRA

At the age of 7 months and over, VRA is typically the behavioral test of choice. It can be used to perform standard audiometry, where frequency-specific hearing thresholds are recorded. However, as a test method, it also has other applications.

VRA can be used to perform speech testing, whereby instead of traditional tones, the child's ability to detect speech sounds is assessed. As this is a test that can be performed via free-field speakers, it is possible to perform VRA with the child's hearing devices in situ in order to assess their aided benefit.

By comparing the results of VRA speech testing with the child wearing their hearing aids to the results of the same test without the hearing aids, it's possible to measure whether the devices are providing clear benefit to the child.

Challenges of aided VRA

Assessing aided benefit via VRA is not without its challenges.

Frequently, at the age at which VRA becomes first possible, the main clinical focus is on repeating unaided audiometry. A period of around six months or longer could have passed since the child's hearing thresholds were initially measured via ABR or ASSR, and so re-establishing thresholds is often prioritized over aided testing in order to confirm whether the hearing levels have remained stable and to assess additional frequencies that may have been tested at that neonatal stage.

This can be further compounded if the patient presents with middle ear effusion, a common presentation in young children, which increases the likelihood of changes to the hearing levels.

Establishing the extent of any fluctuations is important, particularly for a hearing aid wearer who may need adjustments to their amplification settings as a result. If changes to the child's hearing thresholds are noted, whether this is linked to the presence of middle ear dysfunction or not, the importance of establishing whether the underlying sensorineural loss has changed as well, or not, is often deemed the next most important priority.

As a result, performing aided testing is often deemed a much lower priority, and so it can be several assessments, several months later before that opportunity to perform aided testing via VRA arises, particularly if those fluctuations and changes in hearing levels continue over time. This can lead to an even bigger gap between the point of diagnosis or the fitting of those hearing aids and the point at which aided behavioral testing becomes realistically possible.

The end result is that there is a significantly long duration of time for not only clinicians but also for the parents of the child to not have that information or that confirmation as to whether the hearing devices are indeed working effectively.

Establishing aided benefit, or indeed the lack of aided benefit, at an earlier point in time can allow clinicians to adjust the hearing aid in order to provide the best amplification and ensure the best outcomes during what is a highly critical time period in terms of neuroplasticity and speech and language acquisition.

Who should we do aided cortical testing on?

Let’s cover the different target populations below.

Infants aged 3 to 7 months

One of the main groups that can benefit from aided cortical testing is infants and young children. In particular, infants aged 3 to 7 months in order to confirm that their hearing aid fitting has been successful. This group may have been diagnosed following the newborn hearing screening process and had either an ABR or ASSR to identify their hearing thresholds and then move on to the hearing aid fitting process.

However, at this age, they're still too young for behavioral testing such as visual reinforcement audiometry. Furthermore, even when they get to that point of age, it can be some time before aided behavioral testing is done, if at all, because the priority tends to be repeating the hearing test without the hearing aids in.

For this age group, it is really important that we know if their hearing aids are working as intended. It is such a critical speech and language period for these young infants that it's important that we know if the aids are doing the job properly and if not so that we can adjust as necessary.

Young children that cannot do behavioral testing

The aided cortical test is also suitable for any young child who, for whatever reason, cannot or is not doing behavioral testing. It may be that there is some kind of developmental delay, they could have some disabilities or complex needs, or they may simply not be very reliable at the behavioral test being asked of them.

The aided cortical test provides an easy way to see whether the hearing aids are providing the sounds that the patient needs in order to develop their speech and language.

Children with ANSD

Another group of children who are of particular interest for the aided cortical test are those who've been identified as having auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD). These children, again in that 3 to 7+ month age spectrum, may have had their ABR and the ANSD identified at that process but aren't yet ready to perform behavioral testing.

It is known that it is not possible to obtain reliable hearing levels from the ABR results in cases of ANSD and this often results in these children not having hearing aids fitted until behavioral testing is undertaken. There can be fluctuations and variability in the reliability of testing for these children, so often they are not fitted with hearing aids until they are much older.

It is possible to use the aided cortical test in the unaided condition, and the evidence shows that if responses are seen to soft sounds on the aided cortical test, there's likely no worse than a mild hearing loss present in these cases with ANSD (Pearce et al., 2007).

This information can therefore be used to inform whether hearing aid fitting is appropriate and at what levels might be suitable for programming of the hearing aids. Previously, this would have had to wait for behavioral testing, which is often unreliable in this group.

Therefore, earlier intervention is possible with this group of patients in order to support their speech and language development. Often, these children end up being referred for cochlear implantation, so the results of aided cortical testing can inform that process as well.

Infants and young children with a severe to profound hearing loss

Within the infant and young children group, it's important to also highlight those who've been diagnosed with a severe to profound hearing loss. This is a very important group who often end up being referred for consideration of cochlear implantation, but for this they must try hearing aids first.

This group can often be very difficult to condition for behavioral testing because of the raised hearing thresholds present. Aided cortical testing can be used to show whether there's any benefit being derived from the hearing aids, which can then feed into the cochlear-implant-decision-making process.

Cochlear implant users

The aided cortical test can also be used for cochlear implant users. Most of these patients will perform some form of aided testing with their implants in situ, but if this isn't possible for whatever reason, aided cortical testing is an option.

There are some limitations around the likelihood of artifact being present in the aided cortical response, which can contaminate the response. So it's important that clinicians proceed with caution and an awareness of what this artifact might look like and how to be mindful of when it might be present.

Older children that cannot do behavioral testing

Another group of patients who may be suitable for aided cortical testing are older children. Any child who is not performing reliable behavioral testing, for whatever reason, may be suitable for aided cortical testing. This may be due to a genuine difficulty in performing the behavioral test due to some complex needs, developmental delay, disabilities.

Older children with non-organic hearing losses

There is also another group of patients in this older-children group that it is important to be aware of, which are those who present with non-organic hearing losses.

A non-organic hearing loss is where there's a hearing loss presented on the audiogram, and often this is a very reliable hearing loss, but there is an indication in the results or in how the patient is behaving to suggest that the pure tone audiogram thresholds aren't true results.

Sometimes, this group are known as malingerers. They may have normal hearing and be presenting with an untrue hearing loss. They may have a hearing loss which they are then exaggerating. This may be a presentation seen when there are other personal problems in the patient’s life, either at home or at school.

Often, the pure tone audiogram presents with a hearing loss but there might be present otoacoustic emissions, normal speech testing, or the patient’s ability to manage normal conversation in the clinic with the audiologist doesn't match up with the audiometric thresholds.

Adults that cannot do behavioral testing

Adults can also benefit from the aided cortical test. For any patient with complex needs who isn't or cannot perform traditional behavioral testing, the aided cortical test can be a valuable tool in the audiological test battery to help understand some more information about how the patient is managing with or without their hearing aids.

Adult cochlear implant candidates

The aided cortical test can be a valuable test for adult cochlear implant candidates. As is the case for infants, a trial of hearing aids is required before moving on through the cochlear implant candidacy process. Part of that process involves assessing whether the patient is deriving benefit from their hearing aids. The aided cortical test can help provide that alternative information or even simply a cross-check for any behavioral testing that may have been obtained.

Just as in the younger children group, CI users can partake in aided cortical testing with those same limitations around the potential of artifact to be present in the response and the need to proceed with caution when interpreting the waveforms.

When not to do aided cortical testing

Sometimes there may be other tests that are more suitable, such as the ABR, ASSR or threshold cortical depending on what the clinical question is.

Whether one is attempting to establish threshold frequency-specific information or looking for an alternative to speech testing, that will help you to decide which type of test would be most suitable in any given scenario.

Which stimuli should be used for aided cortical testing?

An important consideration when it comes to performing aided cortical testing is around the stimuli used for the test.

The Aided Cortical module on the Interacoustics Eclipse contains a new set of stimuli, which were developed by the University of Manchester and the Interacoustics Research Unit. These are highly frequency specific, with no overlap between them.

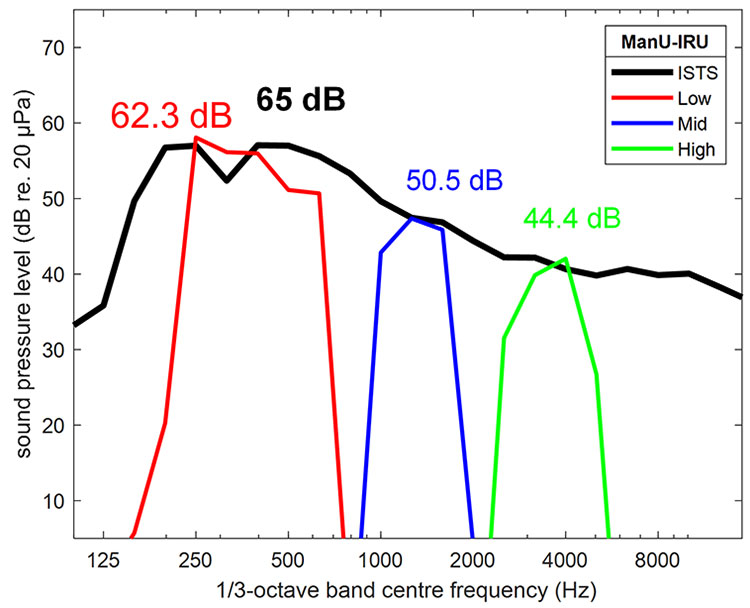

They have also been calibrated with reference to the ISTS signal, meaning that each stimulus is presented at the level that corresponds to its frequency band within the ISTS, which is how natural speech works, with the higher frequencies presented at a quieter level than the lower frequencies (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Source: Stone, M. A. et al. (2019).

These stimuli were not developed from natural speech, but rather were created synthetically. This allows for the excellent frequency specificity of these stimuli. Such a narrow frequency specificity cannot be obtained from natural speech tokens which stimulate a much wider frequency spectrum and run the risk of measuring cortical responses to stimulation of areas of the basilar membrane that don't correspond with the peak frequency region of the stimulus.

The method of calibration for these stimuli aligns them with the ISTS, which means we are presenting sounds to the patient as they would hear them in the real world. This means we are performing an accurate assessment which is representative of how the patient hears speech via their hearing devices.

There are other stimuli available within the aided cortical module. For a deep dive into the differences between these stimuli, please read more here: Which stimuli should be used for aided cortical testing?

’Ladies in the Van study’

The following video is an interview with Dr. Anisa Visram, the lead author of the well-known ‘Ladies in the Van’ study which used the ManU-IRU stimuli with the Eclipse device to perform cortical testing on a group of infant hearing aid users (Visram et al., 2023).

How to set up the equipment for the test

This following video demonstrates how to set up the equipment for the Eclipse Aided Cortical module. You can read the full transcript below.

Transcript

When doing aided cortical testing, it is important that testing is done in a proper environment. Factors such as ventilation and computer fans can mask the noise presented from the free field speaker. It is recommended to perform the test in a quiet environment.

The aided cortical test is primarily performed on infants, small children, and patients with complex needs. The patient should be awake and engaged during testing. Use quiet toys, interesting objects, or silent videos to keep your patient engaged while the test is running. Any screens used should be placed above the free field speaker to ensure the patient is facing toward the source of the stimuli.

Place the patient where the initial calibration was performed, which should be 1.5 m away from the free field speaker. The patient should stay in the same place during testing. When testing infants, either seat them in an appropriate chair or on the lap of their adult. If the position of the patient is changed, the sound field analysis should be repeated to compensate for the change in test environment.

How to use the Sound Field Analyzer

This following video demonstrates how to use the Sound Field Analyzer in the Eclipse Aided Cortical module. You can read the full transcript below.

Transcript

Changes in the test room can affect the stimulus intensity of the aided cortical test. The sound field analyzer compensates for this, ensuring the patient always receives the correct stimulus intensity. We recommend running the sound field analyzer before each aided cortical test you perform.

To use the sound field analyzer, first open the Aided Cortical module. Place the ambient microphone where the patient will sit. The microphone should be level with the patient's ear. Click ‘Sound field analysis’ in the menu on the left. Press ‘Analyze sound field’ in the software.

The speaker will now play a pink noise signal, and the software will measure the intensity of each stimulus compared to the calibrated target. Let the noise signal run for a few seconds, then press ‘Analyze sound field’ again to stop the noise presentation.

If results do not match the calibrated target as seen here, you can press ‘adjust to target’. This will adjust the stimuli to match the calibrated levels. Press ‘OK’ to save your sound field analysis. The adjusted value is also shown on the report.

If you want to use a saved sound field analysis, click the dropdown menu and choose the saved sound field analysis. Adjust to that target and press okay to save. This feature is useful when the equipment is frequently moved between different locations.

Patient preparation

When undertaking an aided cortical assessment, it's important to perform the appropriate patient preparation steps and to ensure the patient is in the optimum state throughout testing.

There are a number of steps to follow to prepare the patient for testing, which will help to maintain the appropriate patient state and support the recording of accurate results for the aided cortical test.

1. Skin preparation and electrode placement

When undertaking skin preparation and electrode placement, the process is identical to ABR, ASSR or threshold cortical assessment. Use electrode gel and some gauze or cotton wool to clean the skin.

As the electrode is a two-channel system, four electrodes will be required for testing. There are many different types available, however it's important to consider the size of these electrodes, particularly if testing on young infants.

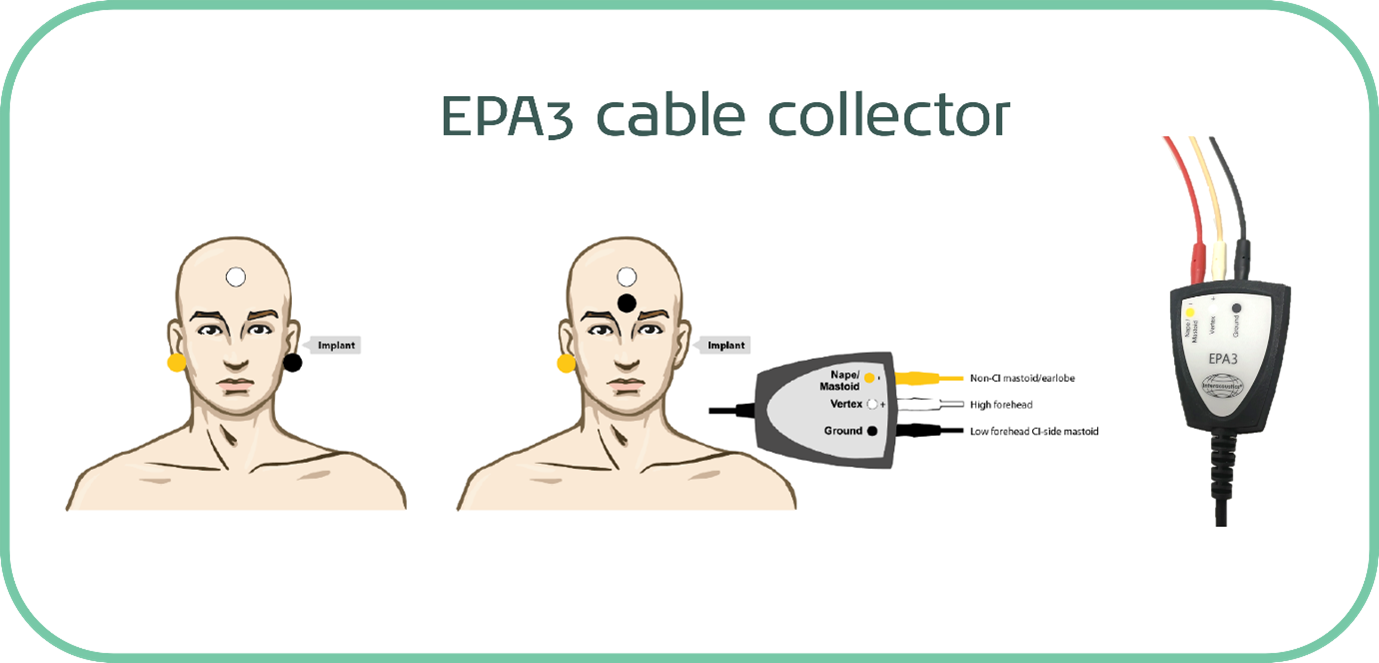

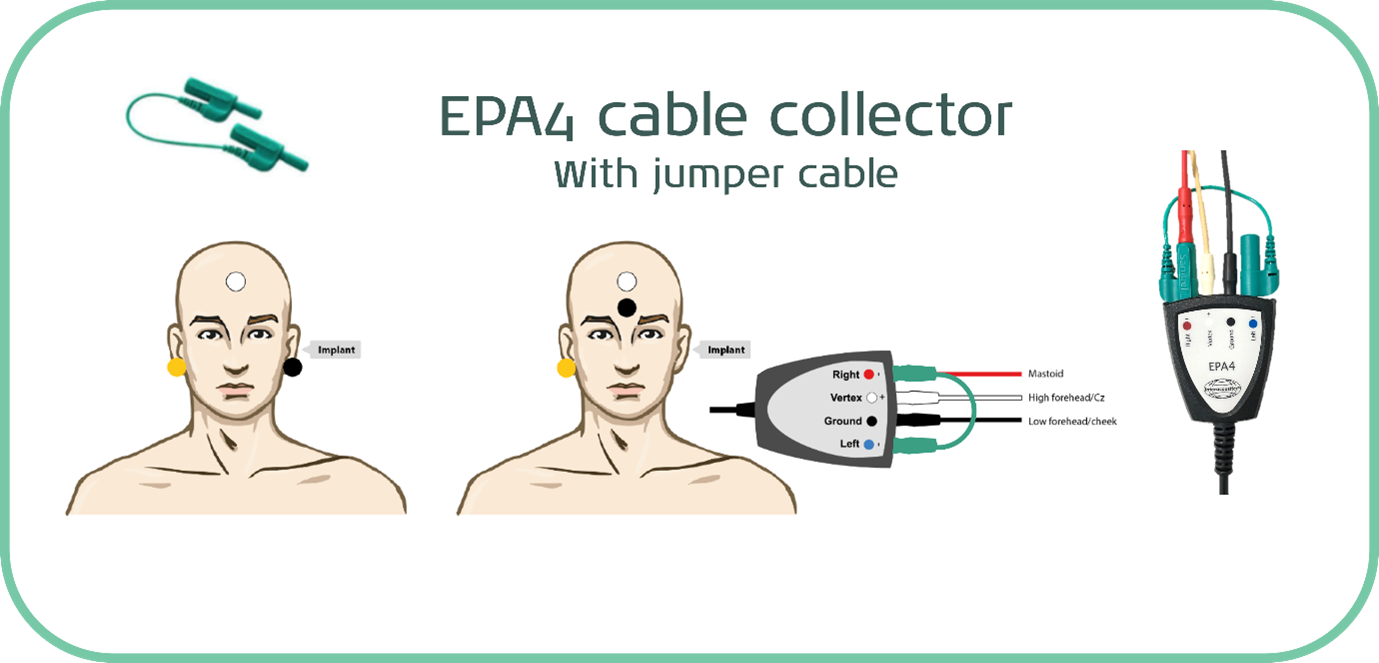

The vertex electrode is placed on the high forehead or true CZ. The ground electrode can go on the low forehead or the cheek, and the two reference electrodes should be placed on the mastoid prominence behind each ear.

Aim for all electrode impedances to be below 5 kiloohms. They should also be balanced across the four electrodes with no more than a 1 kiloohm difference between each electrode.

2. Check the hearing aids

If performing the test in the aided condition, it is vital to check the hearing aids before testing. If the patient, parents or carers report any problems or issues with the devices, it is important to troubleshoot this before running the aided cortical test. Use a hearing instrument test box measurement to check for any faults or problems.

Ear molds, domes or other earpieces should be checked for appropriateness of fit, blockages, or any necessary repairs. When testing infants, new ear molds are needed very regularly, so it can be worth trying to arrange for new impressions to be made ahead of the aided cortical appointment to ensure a good fit on the day of testing.

Also, consider when the hearing aids were last verified. RECDs should be performed regularly for infants, so consider performing an up-to-date verification measurement with the patient's most recent ear molds to ensure the best delivery of sound to the ear.

Lastly, something that may appear to be obvious but can easily be overlooked, is that it is crucial to ensure the devices are switched on, fitted in the ears correctly, and have either new batteries in place or a full charge before starting the aided cortical test.

3. Instruct the parents, carers or the patient

When testing a young child, it's important to give the parents or carers some instructions so that they understand how to help during the test. Discuss with the parent where the child would be seated best. On their own? Using a highchair? Using a small children's chair? Or on the parent's lap?

It's important to explain the nature of the test to the parents or the patient themselves in the case of an older child or adult. They should have realistic expectations as to the likely length of the test, as well as an understanding of what the patient needs to do during the test and what the goal or intention of the test is.

4. Maintain the optimum patient state

Maintaining the optimum patient state is crucial for a successful aided cortical test. Let’s cover ways to do this below.

Engagement toys

For young children and infants, a wide range of engagement toys is absolutely essential. The very youngest of infants require regular changes of toys. The goal is to keep the child seated calmly for the duration of the test without falling asleep or growing too excitable or agitated.

Cartoons or videos

Favorite cartoons or videos on a smartphone or tablet device can be useful. Some clinics have acquired projectors in order to create a cinematic effect within the clinic room whereby they project sensory or children's cartoons onto a wall or projector screen.

Age-appropriate engagement

Any form of engagement should be age-appropriate. For older children or adults this could be reading a book or watching a silent film or TV show with the subtitles on to keep them interested.

Second tester

It is recommended to have a second tester to play and engage with infants and young children so that the first tester can concentrate on the testing process.

Adapt to the situation

Be prepared that what works for a period of time may stop being as successful so you may need to change the engagement activity regularly and frequently.

As the patient has electrodes and cables attached to them, we want to keep their hands busy to stop them pulling on the cables and detaching the electrodes. Remember it is okay to pause the test midway through if the child grows too active or upset.

Monitor the patient’s EEG

In the Eclipse software, it is possible to see the individual patient's EEG and use this to guide the engagement activity. When the EEG lines turn red, this means the sweeps are being rejected. So if there is consistent red, it can be worth pausing the test and trying to alter the engagement activity or have a break for a cuddle or some snacks and reset before continuing on with testing.

Video example

The following video demonstrates the aided cortical test in action on a 6-month-old infant hearing aid wearer.

Interpreting aided cortical waveforms

It is well documented in the literature that infant cortical morphology is highly variable between subjects, as referenced by the BSA Recommended Procedure for Cortical Auditory Evoked Potential Testing (2022). This can make it challenging to accurately detect the presence of a response with confidence.

The BSA Recommended Procedure highlights the value of using objective response detection algorithms for the interpretation of such waveforms. Carter et al. (2010) explored the clinical utility of automatic response detection and found that there was a likely increase in clinicians’ confidence when reviewing cortical responses.

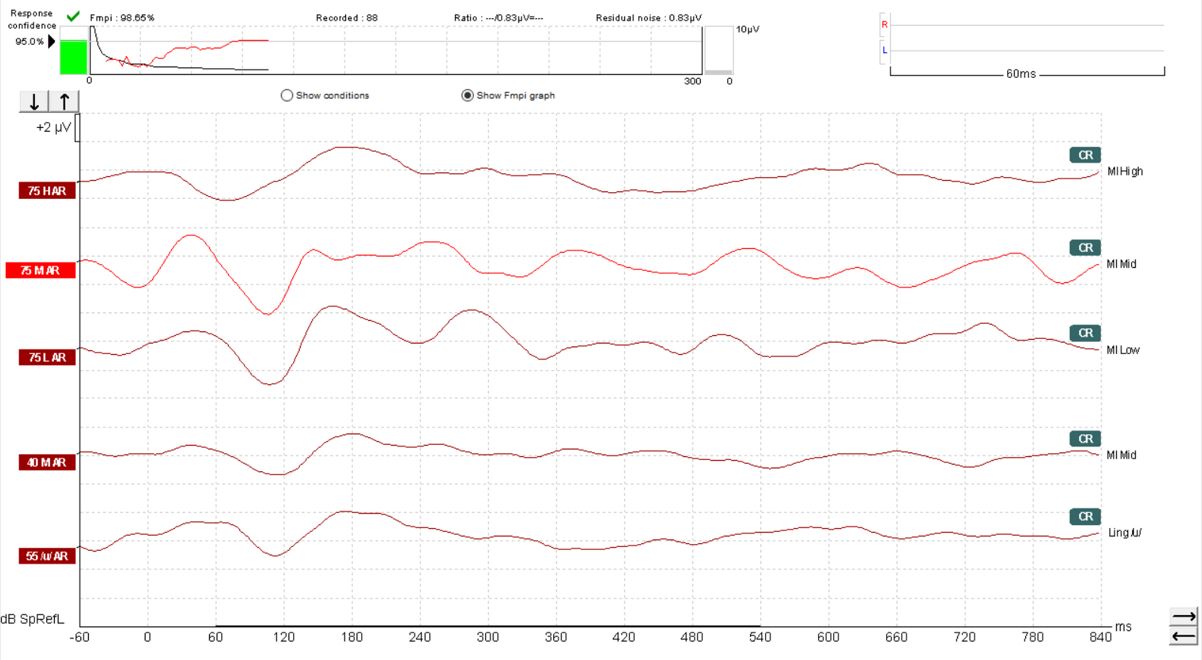

In auditory evoked potentials, detection algorithms have been well established for some time. Fsp evolved into Fmp (which are both well established in ABR testing), and the latest evolution to these algorithms is called Fmpi™.

Fsp and Fmp essentially calculate a signal-to-noise ratio based on the statistical variance of the measured average overall waveform in relation to the estimated residual noise of the waveform. Fsp estimated the residual noise based on just one single point of data on the waveform.

Fmp extended this to making use of multiple points of data on the waveform (5 to be precise). Fmpi also calculates a signal-to-noise ratio, but now all of the measured data points on the waveform are included in the calculation. In the case of an aided cortical measurement, this comes to 250 data points.

Furthermore, the individual listener’s brain activity (EEG) is taken into consideration with Fmpi, which doesn’t happen in Fsp or Fmp where a conservative estimation of the EEG is used. The end result is that, with Fmpi, the detection of a cortical response can be established with fewer numbers of sweeps, and thus less time, than Fsp or Fmpi in the majority of patients.

The default setting with the Eclipse Aided Cortical module is for Fmpi response detection to be set at 95%. However, 99% can also be selected should you prefer. In Figure 10, we can see a response confidence Fmpi value of over 99% has been achieved within 66 sweeps.

Learn more: How to interpret aided cortical waveforms

Hearing aid management

The results obtained from the aided cortical test can be used to guide hearing aid management for an individual patient. It is important to remember that any changes and adjustments to hearing aid settings should be based on the fullest amount of information available, including feedback from parents, carers and other significant people involved with the patient, such as teachers and speech and language therapists.

When and when not to change hearing aid settings

It is also important to be mindful of when it is appropriate to make changes to the hearing aid settings and when not to. In particular, when considering making changes or adjustments based on non-responses that indicate that a sound may not be heard by the patient, this should be made based on consistent and repeatable non-responses, not just one waveform. This is to ensure that any non-response detected is a genuine non-response.

The data gathered by the Ladies in the Van study highlights that repeat testing increases the likelihood of detection. Upon repeat testing, sensitivity values published in that study showed an increase from 80% to 94% for the mid-frequency stimulus, and from 60% to 79% for the high-frequency stimulus. This study also looked at the impact of infant vocalizations, and found that the more vocal the child, the more likely it was that a non-response would be detected. As already mentioned, changes to the hearing aid provision or settings must be made alongside other supportive information.

Test battery approach

Adopting a test battery approach allows for additional data and results to corroborate the findings of the aided cortical test. Validated questionnaires such as LittlEars, PEACH and TEACH can be used. Additional testing, such as tympanometry, can indicate whether there's any middle ear dysfunction that could explain unexpected results on the aided cortical test.

Performing HIT box measurements can help rule out any hearing aid faults that might also interfere with the results. Ensuring an up-to-date RECD has been performed, ideally with new ear molds, is also important to ensure there's no leakage from the hearing aids, and that the correct amplification is being provided for use during the cortical test.

Lastly, parent or carer feedback should not be underestimated. As the people spending the most amount of time with the patient, they can provide a valuable perspective on how well the hearing aids are working. Likewise, any changes or adjustments to the patient's amplification should be made with informed parental or carer consent to ensure they are aware of the risks of and are able to detect any possible loudness discomfort.

National guidelines

As it stands, there are currently no national guidelines for how to adjust hearing aid settings based on the aided cortical results using the Eclipse system and the available stimuli. However, there are two broad options available if it is deemed that the current level of amplification is insufficient for the patient.

1. Increase the hearing aid gain

The hearing aid gain can be increased; however, it is unclear by how much this should be adjusted to be certain of effective change. As a result, the guesswork involved in increasing the gain can lead to loudness discomfort.

2. Reprogram the audiogram

A far better option is to reprogram the audiogram to provide louder amplification. In doing so, it is possible to make use of validated prescription formulae, which provide a higher degree of certainty by providing a target to be matched during the verification process. The use of REMs or RECD measurements ensures we have control over the loudness level of the device through the MPO target and loud input level.

This approach of reprogramming the audiogram as opposed to increasing the gain is seen in the Australian guidelines for aided cortical testing (Punch et al., 2016). Within this protocol, it is recommended to revise the hearing thresholds by certain levels based on the cortical results.

However, it should be noted that these recommendations adopt a one-size-fits-all approach whereby the full audiogram is adjusted based on the results obtained rather than addressing specific frequency regions of the audiogram. This is likely due to the poor frequency specificity of the stimuli used.

Further aided cortical testing

Once hearing aid adjustments have been made, it is required to perform further aided cortical testing to validate the newly prescribed amplification. In cases where responses are not detected to the increased amplification based on the newly programmed audiogram, then clinicians are guided to refer to the speech-o-gram to assess whether audibility is to be expected.

If the speech-o-gram indicates that the stimuli presented via the aided cortical test are not likely to be audible, then the results align with the expectations for the patient's audibility and hearing aid provision. If the speech-o-gram indicates that the stimuli are likely to be audible, then the results of the aided cortical test do not align with expectations, and this may be a case of false non-responses being detected. In this instance, clinicians are guided to refer to the PEACH questionnaire to guide hearing aid management decisions instead.

Approach with ManU-IRU stimuli

The one-size-fits-all approach used by the Australian program does not work for the ManU-IRU stimuli due to their vastly greater frequency specificity. The full audiogram range should not be changed based on the results obtained, but rather a more frequency-specific approach should be adopted.

If aided cortical responses are not detected, then it is recommended to refer to the REM traces and inspect the areas that relate specifically to the individual stimuli and levels tested.

If, for the non-response stimulus and level in question, the hearing aid output in that region is greater than 10 dB above threshold, then audibility can be expected.

If, instead, the hearing aid output of the REM traces is not greater than 10 dB above threshold, then the non-response of the aided cortical test aligns with the poor audibility expected from this hearing aid fitting. The stimulus in question may not be audible due to the degree of hearing loss and the type of device provided, and the patient's onward management should be considered accordingly.

Complex testing scenarios

Below, we’ll cover complex aided cortical testing scenarios.

1. Unilateral or asymmetrical losses

When performing the aided cortical test on a patient with a bilateral hearing loss, fitted with hearing aids on both ears, the test is relatively straightforward. However, when considering those patients with an asymmetrical or unilateral loss, matters become slightly more complicated and require some additional considerations.

How you approach the test for this patient group will depend on the configuration of their hearing loss and how they are aided.

Asymmetrical hearing loss with only one aidable ear

If the patient has a dead ear, or almost no usable hearing on one ear and therefore hasn't been fitted with a device on that side, but has an aidable loss on the other ear which has been fitted with a hearing aid, then it is simple enough to perform the aided cortical test in the same way as you would for a patient with two hearing aids. No adjustments are required.

In this instance, you would perform the test in the aided right or left condition depending on which ear has the device fitted and simply make it clear in the notes or comments as to the status of the opposite ear.

Asymmetrical hearing loss with normal hearing in the unaided ear

If the patient has normal hearing in the unaided ear, then it is important to consider if there is value to be obtained from performing the aided cortical test. This is where we should remember what the clinical question is, and which answers we are seeking from potentially performing this test.

If, as is the case for most young infants and children, the clinical question is about whether the child can access speech sounds in the real world, then we can be confident that their normally hearing ear will support this. The provision of a hearing aid in the other ear in such a scenario is typically designed to provide localization cues and help in managing background noise.

It is important to have realistic expectations regarding the efficacy of a unilaterally fitted hearing aid. Depending on the extent of the loss, this device may not be supplying most of the speech and language information that the child will access. As a result, many clinicians opt not to perform aided cortical testing on these cases as the usefulness of the information obtained may be minimal.

Bilateral asymmetrical hearing loss

If the patient has a bilateral hearing loss, but this is asymmetrical, then we need to consider the extent of the loss. If the better ear has not been aided, perhaps because the hearing loss is very mild, then performing the aided cortical test in their real-world scenario, with the hearing aid in situ on the poorer ear, can help to confirm whether the patient is accessing speech sounds as they would be hearing on a day-to-day basis in the real world. If the results are not satisfactory, then this may point towards aiding the better ear.

2. Assess the aided benefit provided by one single device

If there is a need to perform the aided cortical test to assess the aided benefit provided by one single device at a time, then there are some different options as to how to do this. Essentially, the goal is to remove the opposite device or ear from being able to detect the stimuli delivered and from contributing to the response generated.

Occlude the non-test ear

One option is to occlude the non-test ear using a foam earplug or their own earmold using something to block the sound hole.

Remove the patient’s better ear hearing aid

Another possibility is to simply remove the patient's better ear hearing aid from their ear for the duration of the test. However, this increases the risk that sound may be detected by this ear (depending on the extent of the loss).

Ear defenders

Using additional ear defenders over the non-test ear, whether it has been occluded or not, can help reduce the likelihood of the stimuli being detected.

Mask the non-test ear

Another option which many clinicians have queried, is the possibility of using a separate audiometer with which to deliver masking noise via a transducer to the non-test ear. However, there are a few practicalities which make this challenging.

Tolerance

Firstly, the patient groups who typically undergo aided cortical testing may not tolerate an additional transducer with an additional amount of noise being presented.

Frequency range

Secondly, traditional narrowband masking noise is unlikely to be broad enough to cover the frequency range of the speech stimuli being presented. White noise or speech noise are more likely to have a sufficient bandwidth.

However, it is important to ensure these have been calibrated on the audiometer used and to understand how they may have been calibrated and any associated offset values.

Guidelines

Thirdly, there are no current guidelines or recommendations as to how to calculate the level of masking noise required to effectively mask a speech stimulus delivered via the sound field. There are risks to using the incorrect level of masking noise.

Not enough masking noise may not effectively prevent the non-test ear from being able to detect the stimulus and contribute to the generation of a response. Too much masking noise may lead to cross-hearing, whereby the device on the test ear is able to detect the masking noise, and this can lead to the stimulus being masked by the test ear as well and may prevent a response from being generated.

As a result, until such guidelines are developed, it is currently recommended to not use masking noise during the aided cortical test.

3. Cochlear implants

In addition to hearing aid users, patients who have been fitted with cochlear implants can also benefit from the aided cortical test. Performing this test on cochlear-implant patients comes with some unique challenges which need to be understood and considered.

Artefacts

The main challenge facing this cohort is the interference or radio frequency noise that can be generated by the device itself. This can be detected by the recording electrodes, and lead to artefact in the waveform, which can make it difficult to accurately interpret whether a true response is present or not.

There are several published studies detailing the use of aided cortical responses in patients fitted with cochlear implants. Kosaner et al. (2018) tested 45 children who had been unilaterally implanted with MED-EL devices. They found artefact in only 8 traces from 3 of the children tested.

Of the 108 adult participants tested by Távora-Vieira et al. (2022), there were no reported artefacts from the unilaterally implanted MED-EL devices. Another study by Távora-Vieira et al. (2021) compared electronically evoked cortical potentials with acoustically evoked cortical potentials in unilaterally implanted adult patients using MED-EL devices.

Choi et al. (2019) reported a study of 20 participants. This adult cohort included unilaterally and bilaterally implanted patients, who were all tested with just one implant switched on at a time. These participants were fitted with a combination of Cochlear and Advanced Bionics devices, and although more artefacts were found in the AB devices, the artefacts produced by the Cochlear devices were larger in amplitude.

It is essential that any clinician performing the aided cortical test with implanted patients is aware of the potential for artefacts being present in the waveform, knows how to identify these, and understands the impact that such artefacts can have upon the detection and interpretation of responses.

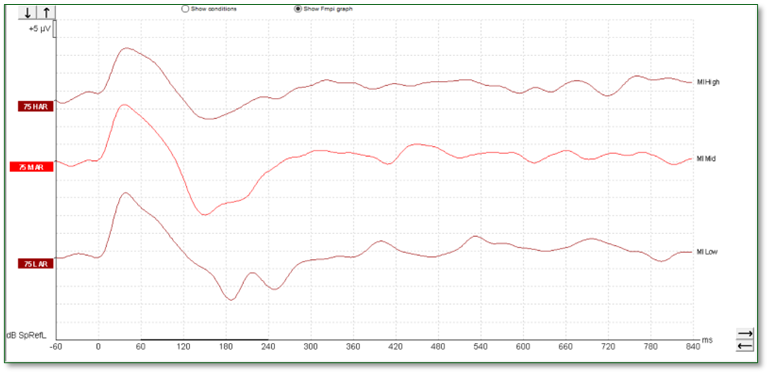

The waveforms in Figure 11 were recorded from a young patient who had been fitted with a cochlear implant. There is no apparent artefact in these traces and the morphology is very similar to that seen in hearing aid users.

We can see artefacts in Figure 12. Unfortunately, these artefacts can look quite similar to cortical responses. Key warning signs that an artefact is present is the slightly triangular or squarish shape present in the waveform. We can see the first positive inflection appears much earlier in latency than we would expect for a cortical response. Here it is just after 0 milliseconds.

Unfortunately, the Fmpi™ response detection algorithm cannot differentiate between artefact and genuine response. In Figure 12, the Fmpi value was detected at over 95%, but it is not possible to be certain as to whether this was detected due to artefact, a genuine response being present, or a combination of both.

Examining suspected artefacts

It is possible to examine any suspected artefacts by removing the display filter settings.

In Figure 14, we can see how the peak has become flat and square-shaped. A true cortical response would not modify in this way.

In Figures 15 and 16, we can see a cortical response without artefact. When removing the high-pass filter setting, there is very little change to the shape of the positive inflections. When testing patients with cochlear implants, it is important to explore these elements of the waveform to help distinguish between genuine responses and artefacts.

Reducing artefacts

There have been several studies which have looked at different methods for reducing artefacts in cortical assessments. These are summarized by Choi et al. (2019), largely focusing on signal processing and analysis techniques. There are, however, some steps that can be taken to minimize artefact in evoked potential recordings in the clinical test setup.

The main method for minimizing the likelihood of artefact in the waveform is to reduce the chance for electrical interference from the device to be detected by the recording electrodes.

The most successful way to achieve this is to simply increase the distance between the implant and the recording electrodes. This can be done by opting for a three-electrode montage with the reference electrode on the contralateral mastoid to the implant. For those of you familiar with eABR testing, this is the same setup.

It is also possible to use a jumper cable with a four-electrode cable collector, which effectively removes one of the electrodes from play and allows you to perform the testing with just three electrodes.

This is easily achievable when testing a unilaterally implanted patient and is the methodology of choice in most published research papers into aided cortical testing with cochlear implants.

For a bilaterally implanted patient, it is possible to explore testing with four electrodes and both implants switched on, but if artefact is present in the waveforms, then switching to unilateral assessment with three electrodes is the recommended process in these cases.

Which stimulus to use?

A further consideration when performing the aided cortical test on patients fitted with a cochlear implant surrounds which stimulus to use. The ManU-IRU stimuli are a particularly appropriate choice for hearing aid users. This stimulus set was designed with hearing aids in mind, hence calibration alignment with the ISTS.

Furthermore, these stimuli have been validated for use with hearing aids and data is available regarding the sensitivity of the test with these stimuli for hearing aid users from the Ladies in the Van study.

However, no such data currently exists regarding cochlear implants and the likelihood of being able to detect responses when performing the aided cortical test. As such, caution is urged when interpreting the results of this test, particularly for any absent responses.

For cochlear-implant patients, until more data becomes available regarding the ManU-IRU stimuli, it may be more suitable to make use of the HD-Sounds. Most research papers which have investigated cortical testing on implanted patients have used the /m/, /g/ and /t/ stimuli that were the predecessors to the HD-Sounds. The unfiltered version of the HD-Sounds corresponds most closely to those original stimuli. However, it is important to be aware of the poor frequency specificity of these sounds.

There are research papers which propose cochlear implant programming strategies based on how the electrodes correspond to these stimuli and have explored methods for adjusting the T and C levels. This is an exciting area for further research to build and develop the evidence base to support the clinical utility of the aided cortical test for cochlear-implant patients.

4. Auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder

There has been a lot of interest in the clinical application of cortical testing for patients with Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder, also known as ANSD. This is generally because cortical testing provides information about where the sounds are detected at the furthest part of the auditory pathway, the cortex.

The pathophysiology of ANSD relates to the connection between the cochlea and the neural pathway and is typically identified using ABR testing.

The issue with ABR testing is that although it can help in the identification of ANSD, the results don't tend to correlate with behavioral testing or how well the patient can hear in the real world.

ABR results in cases of ANSD can show absent morphologies at maximum presentation levels, which can look like severe to profound hearing loss. However, it is known that behavioural testing can and does often show much better thresholds.

The problem with relying on behavioural thresholds to understand the degree of hearing loss, and therefore the best method of intervention, is that for children it may be several years after their diagnosis as an infant before reliable behavioural thresholds can be obtained, and accurate amplification can be provided.

This can lead to the child missing out on receiving vital auditory information during those early years of crucial speech and language development. There is evidence that cortical auditory evoked potentials, also known as the auditory late response, are less affected by ANSD than ABRs, as they are less reliant on timing to elicit responses.

Threshold cortical testing can be useful for older children and adults with ANSD to establish frequency-specific threshold information. However, this is not recommended for infants and younger children, due to the immature cortex and resulting lack of robust waveform morphology.

This is further exacerbated by challenges in reducing the patient noise sufficiently to record the small amplitude responses around threshold.

Research on cortical testing in ANSD patients

Instead, for this patient group, there has been more attention given to cortical testing using speech-like stimuli, which are presented via the sound field. The results obtained can help inform decisions about earlier provision of hearing aid amplification than was traditionally possible, and onward referral for cochlear implantation.

Rance et al. (2002)

Rance et al. (2002) compared two cohorts of children, one with ANSD and one with sensorineural loss. They performed speech testing and unaided cortical testing using a speech-like stimulus and a tonal stimulus. Amongst a range of findings, of the 18 children with ANSD, cortical responses were recordable in 50%.

The findings of this study confirm that cortical waveforms can be recorded in ANSD patients but also raise a note of caution regarding the interpretation of non-responses. As is the case for any children undergoing cortical testing, it is important to remain mindful that an absent response does not always indicate that the patient cannot hear the presented stimulus.

Pearce et al. (2007)

In a paper by Pearce et al. (2007), a case study was presented of an infant diagnosed with ANSD who then went on to have unaided cortical testing performed using speech stimuli to help guide decisions regarding whether amplification was warranted. This child had absent ABR responses to 500 Hz and 2 kHz at the maximum testable levels, but present DPOAEs across the full tested frequency range.

The parents reported that the child was responsive to sounds around the home, such as familiar voices and the stereo. Unaided cortical testing showed repeatable responses to all three stimuli at a level of 65 dB SPL. It is worth highlighting the relatively poor frequency specificity of the stimuli used.

Based on the results obtained and the parental reporting, it was possible to exclude a severe hearing loss. However, a mild to moderate loss was still possible.

As a result, it was decided to proceed with amplification using an audiogram that would not cause cochlear damage even if the thresholds were found to be normal. This patient's unaided cortical testing was performed at 7 weeks corrected age, allowing for hearing aid fitting shortly after.

In contrast, reliable behavioral thresholds via visual reinforcement audiometry could not be obtained until two and a half years of age. Typically, behavioral testing can be performed reliably at a much younger age than this, however it is not uncommon to see a delay in obtaining results in ANSD cases.

Furthermore, this child was born at 28 weeks gestation age. Prematurity and ANSD are often seen together, and a degree of developmental delay can result, leading to delays in being able to perform behavioral testing.

Punch et al. (2016)

A paper published by Punch et al. (2016) summarized the Australian Hearing protocol for fitting hearing aids to infants diagnosed with hearing loss, which were the guidelines followed in the previous study.

These guidelines specifically highlight that in cases of ANSD, any decision to provide hearing aids and the estimated audiogram levels used should be based on all the available clinical information, including behavioral testing, parental reporting, for example using the validated PEACH questionnaire, and unaided cortical testing results.

In addition to providing useful information regarding the decision to aid, the Australian Hearing protocol also advises on the use of aided cortical testing for those patients with ANSD who have been fitted with hearing aids. This can add valuable information regarding decisions surrounding consideration for cochlear implantation, which many ANSD patients are deemed suitable for.

Final thoughts on cortical testing in ANSD patients

Patients with ANSD continue to be challenging to diagnose and manage. Cortical testing in both the unaided and aided condition, using speech-like stimuli, can provide useful information in both the decision-making process relating to amplification and the validation of amplification provided.

Caution must be used when interpreting non-responses, as there are scenarios where cortical responses may not be present, but the stimuli may in fact be audible. It is essential to adopt a test-battery approach, whereby multiple sources of information and test results are used to corroborate each other and inform the most suitable management for each individual patient.

Related courses

- Getting started: Aided cortical testing

- Beyond the basics: Aided cortical testing

- Perfecting your test technique: Aided cortical testing

References

British Society of Audiology. (2022). Recommended procedure: Cortical auditory evoked potential (CAEP) testing (Version 2, OD104-40). British Society of Audiology.

Carter, L., Golding, M., Dillon, H., & Seymour, J. (2010). The detection of infant cortical auditory evoked potentials (CAEPs) using statistical and visual detection techniques. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 21(5), 347–356.

Choi, S. M. S., Wong, E. C. M., & McPherson, B. (2019). Aided cortical auditory evoked measures with cochlear implantees: the challenge of stimulus artefacts. Hearing, Balance and Communication, 17(3), 229–238.

Dillon, H. (2023a). Phoneme levels for use in evoked cortical response measurement [Internal report].

Dillon, H. (2023b). Preparation of speech stimuli for cortical testing [Internal report].

Dillon, H., Carter, L., Seymour, J., & Golding, M. (2006). Automated detection of cortical auditory evoked potentials. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Audiology, 28(Suppl.), 20.

Golding, M., Dillon, H., Seymour, J., & Carter, L. (2006). Obligatory cortical auditory evoked potentials (CAEPs) in infants — A five year review. In National Acoustic Laboratories Research & Development Annual Report 2005/2006 (pp. 15–19). National Acoustic Laboratories.

Golding, M., Purdy, S., Sharma, M., & Dillon, H. (2006). The effect of stimulus duration and interstimulus interval on cortical responses in infants. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Audiology, 28, 122–136.

Golding, M., Pearce, W., Seymour, J., Cooper, A., Ching, T., & Dillon, H. (2007). The relationship between obligatory cortical auditory evoked potentials (CAEPs) and functional measures in young infants. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 18(2), 117–125.

Kosaner, J., Van Dun, B., Yigit, O., Gultekin, M., & Bayguzina, S. (2018). Clinically recorded cortical auditory evoked potentials from paediatric cochlear implant users fitted with electrically elicited stapedius reflex thresholds. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology, 108, 100–112.

Pearce, W., Golding, M., & Dillon, H. (2007). Cortical auditory evoked potentials in the assessment of auditory neuropathy: two case studies. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 18(5), 380–390.

Punch, S., Van Dun, B., King, A., Carter, L., & Pearce, W. (2016). Clinical Experience of Using Cortical Auditory Evoked Potentials in the Treatment of Infant Hearing Loss in Australia. Seminars in hearing, 37(1), 36–52.

Rance, G., Cone-Wesson, B., Wunderlich, J., & Dowell, R. (2002). Speech perception and cortical event related potentials in children with auditory neuropathy. Ear and hearing, 23(3), 239–253.

Scollie, S., & Glista, D. (2012). The Ling-6(HL): Instructions. The University of Western Ontario.

Scollie, S., Glista, D., Tenhaaf, J., Dunn, A., Malandrino, A., Keene, K., & Folkeard, P. (2012). Stimuli and normative data for detection of Ling-6 sounds in hearing level. American journal of audiology, 21(2), 232–241.

Stone, M. A., Visram, A., Harte, J. M., & Munro, K. J. (2019). A Set of Time-and-Frequency-Localized Short-Duration Speech-Like Stimuli for Assessing Hearing-Aid Performance via Cortical Auditory-Evoked Potentials. Trends in hearing, 23, 2331216519885568.

Távora-Vieira, D., Mandruzzato, G., Polak, M., Truong, B., & Stutley, A. (2021). Comparative Analysis of Cortical Auditory Evoked Potential in Cochlear Implant Users. Ear and hearing, 42(6), 1755–1769.

Távora-Vieira, D., Wedekind, A., Ffoulkes, E., Voola, M., & Marino, R. (2022). Cortical auditory evoked potential in cochlear implant users: An objective method to improve speech perception. PloS one, 17(10), e0274643.

Visram, A. S., Stone, M. A., Purdy, S. C., Bell, S. L., Brooks, J., Bruce, I. A., Chesnaye, M. A., Dillon, H., Harte, J. M., Hudson, C. L., Laugesen, S., Morgan, R. E., O'Driscoll, M., Roberts, S. A., Roughley, A. J., Simpson, D., & Munro, K. J. (2023). Aided Cortical Auditory Evoked Potentials in Infants With Frequency-Specific Synthetic Speech Stimuli: Sensitivity, Repeatability, and Feasibility. Ear and hearing, 44(5), 1157–1172.

Presenter

Get priority access to training

Sign up to the Interacoustics Academy newsletter to be the first to hear about our latest updates and get priority access to our online events.

By signing up, I accept to receive newsletter e-mails from Interacoustics. I can withdraw my consent at any time by using the ‘unsubscribe’-function included in each e-mail.

Click here and read our privacy notice, if you want to know more about how we treat and protect your personal data.