Subscribe to the Interacoustics Academy newsletter for updates and priority access to online events

Training in Pediatrics

-

Course: Advances in Pediatric Vestibular Assessment

-

The Role of Diagnostic Tests of Hearing and Balance in the Pediatric Cochlear Implant Patient Journey

-

Consequences of Not Performing Balance Testing in Infants with Sensorineural Hearing Loss

-

Assessing Vestibular Function in a Child

-

Pediatric Vestibular Disorders and Syndromes

-

The Prevalence of Vestibular and Balance Problems in Children with Hearing Loss

-

vHIT in the Pediatric Population

-

Paediatric vestibular assessment (Rotational chair focus)

-

Integrating balance assessments into your pediatric service

5 things in 5 minutes: How to screen for pediatric vestibular loss

Description

Written by Kristen Janky, Au.D., Ph.D., CCC-A

You should suspect children of having vestibular loss if they have complaints of dizziness, if they have severe or profound sensorineural hearing loss, if that hearing loss is acquired or progressive, and if there is any co-occurring gross motor delay.

One question I often get is: Are there simple screening techniques in clinical practice that might identify a child at risk for vestibular involvement?

YES! I typically recommend five things you can do in less than five minutes to identify children at risk for having a vestibular disorder.

1. Ask if the child is having dizziness

First, ask if the child is having any dizziness. Children can have the same etiologies of dizziness as adults, with the leading diagnosis being vestibular migraine [1]. Therefore, the presence of dizziness can be a risk factor for an underlying vestibular disorder.

If the child is too young to answer whether they are dizzy, then ask for parental concern, as this is a significant indicator for vestibular dysfunction [4].

2. Determine degree and onset of hearing loss

Second, determine the degree and onset of hearing loss through audiometric evaluation.

Sensorineural hearing loss is a risk factor for vestibular involvement, but there are two additional factors. One, hearing loss that is severe to profound, and two, hearing loss that is progressive or acquired, are also risk factors for vestibular involvement [2-5].

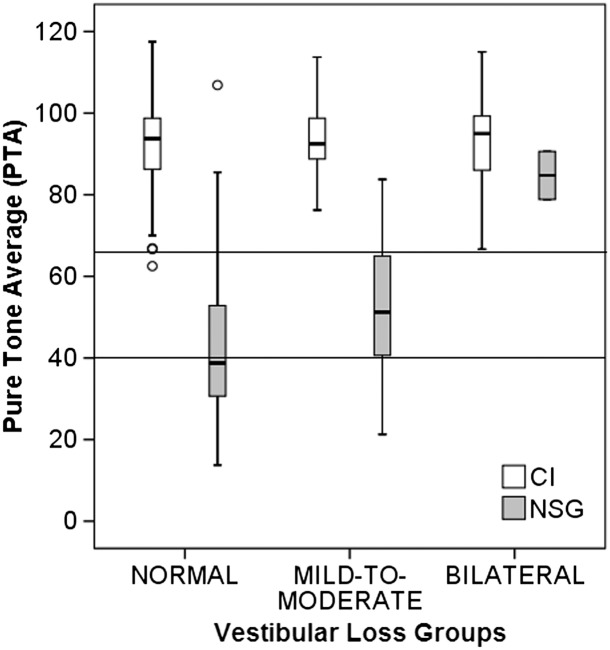

Here are some data from a study we published in 2018 investigating the relationship between audiometric outcomes and vestibular loss severity [4]:

In this cohort, all the children had hearing loss but were put into groups of normal vestibular function, mild to moderate (unilateral) vestibular involvement, or bilateral vestibular involvement.

Drawing a line at roughly 66 dB encompasses all the kids who have bilateral vestibular involvement and most of the kids who have unilateral involvement.

This tells us that using degree of hearing loss as a risk factor for vestibular involvement identifies most of the kids who have vestibular involvement. It's not a perfect predictor, as we have seen small numbers of kids since this publication with normal to near normal hearing with bilateral vestibular loss, but it helps to identify most and justifies the use of other predictors.

3. Take a gross motor skill case history

Third, take a gross motor skill case history.

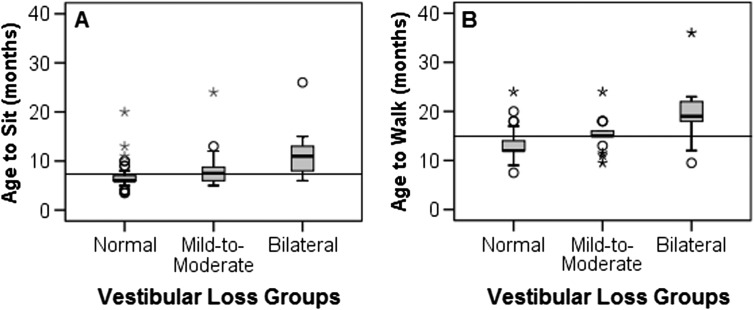

Children are more likely to have vestibular loss if they sit later than 7.25 months or walk later than 14.5 months. In Figures 2A and 2B, we have children with hearing loss, separated into groups of those with normal vestibular function, mild to moderate (unilateral) vestibular involvement, and then bilateral vestibular involvement [4].

Kids who have either unilateral or bilateral vestibular involvement sit (2A) and walk (2B) later than kids with normal vestibular function. The more severe the vestibular involvement, the more severe the delays in gross motor milestones are.

It is important to note that some of these values overlap with normal expectations. The World Health Organization published normative data for acquiring some of these gross motor skills [6].

The normative data for sitting without support ranges from 3.8 to 9.2 months, and our cutoff criterion is 7.25 months. If a child sits independently at 8 months, that doesn't necessarily mean they're in the abnormal range but raises a red flag for the potential presence of an underlying vestibular disorder.

Similar with walking independently, the World Health Organization recommends that 8 to 17.5 months is considered the normal range, whereas we consider the presence of an underlying vestibular disorder if a child walks later than 14.5 months.

Children are also more likely to have vestibular loss if their parents express concern for their child's gross motor skill acquisition [4].

The questions you can ask parents very quickly are:

- At what age did your child sit independently?

- At what age did your child walk independently?

- Are you concerned about your child's gross motor skill acquisition?

These questions take a few seconds and can be helpful in identifying whether a child has an underlying vestibular disorder.

4. Single leg stance

Fourth, have school-aged children complete the single-leg-stance test with eyes closed.

You ask the child to:

- Stand on their dominant leg (you can determine this by asking the child to put on a pair of pants or ask them which leg they would use if they were to kick a soccer ball).

- Bend their opposite knee at 90 degrees.

- Put their hands on their hips.

- Ask them to close their eyes.

- And stand on one leg for a maximum of 10 seconds.

Stop the timing if the child opens their eye(s), puts the non-standing foot down, or moves their standing leg. The cutoff is four seconds [7-8].

Children who have normal vestibular function can stand on one leg with their eyes closed for more than four seconds. Children who have vestibular involvement, whether unilateral or bilateral, cannot do this for four seconds.

This is a fast and effective screening tool. However, note that the single-leg-stance test is only effective for school-aged children. Children cannot complete the single-leg-stance test with eyes closed until roughly age seven.

5. Bedside head impulse test

Fifth, complete a bedside head impulse test.

For this test, you do high-acceleration, unpredictable head thrusts in the plane of the horizontal canal. The child will look at a target, which is typically your nose (consider putting a sticker on your nose), and you move their head rapidly back and forth.

If their eyes remain fixed on the target in response to these high acceleration head impulses, vestibular function is normal. If their eyes drift slowly with their head and then snap back to the target (corrective saccade), vestibular function is abnormal [9].

The head impulse test is typically positive once the caloric weakness is greater than 40 to 50 percent. Unfortunately, the bedside head impulse test is not sensitive for identifying mild vestibular involvement but is a great screening tool [10].

The bedside head impulse test can be difficult to interpret, especially for new clinicians, as it relies on your ability to observe a catch-up saccade. A more accurate evaluation, if the child can tolerate wearing video goggles, would be utilizing a computerized video head impulse test system that can measure vestibulo-ocular gain and identify the presence of saccades.

Additional tests to screen for vestibular involvement

There are additional things you can do to screen for vestibular involvement.

Modified clinical test of sensory integration on balance (mCTSIB)

First, is the modified clinical test of sensory integration on balance (mCTSIB).

For the mCTSIB, the patient maintains balance with arms crossed or at their hips while standing in the following conditions:

- Hard surface, eyes open.

- Hard surface, eyes closed.

- Foam surface, eyes open.

- Foam surface, eyes closed.

They perform each condition for 30 seconds. At the end of the trials, you sum them all up for a maximum score of 120 seconds. Children who score less than 100 are at increased risk of having a vestibular disorder [9].

Dynamic visual acuity (DVA)

Second, is dynamic visual acuity. This is a comparison of visual acuity while the head is still versus moving.

For a bedside evaluation, you can use a Snellen eye chart with either letters or shapes. You ask the child to read down the eye chart to the smallest line that they can see clearly. When they miss a letter, you go above that line and that is their static visual acuity threshold. Please note that if the child wears corrective lenses, they should wear these for the entire test.

You then stand behind the child and move their head back and forth at roughly two hertz and measure their visual acuity with the head in motion. Anything greater than a two-line change in visual acuity is consistent with vestibular involvement.

If the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) is working and the vestibular system is intact, an individual should see roughly the same with their head still as they do with head in motion. For individuals with bilateral vestibular loss, it's typical to see anywhere from a five-to-six-line change in acuity when we go from head still to head in motion.

There is a computerized version of this evaluation that measures head velocity during the testing while the patient is wearing a head sensor. Computerized DVA allows for standardized evaluation and easy comparison between sessions.

Conclusion

To summarize, Table 1 displays the red flags for pediatric vestibular involvement using the “5 things in 5 minutes” framework. Other confirmatory tests include the mCTSIB and the dynamic visual acuity test.

If any of these red flags point toward possible vestibular involvement, it is recommended that the child complete a diagnostic evaluation, including, but not limited to:

- Caloric testing

- Functional VOR testing

- Rotational chair testing

- Videonystagmography (VNG)

- Video head impulse testing (vHIT)

- Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs)

| Things to consider | Red flag for pediatric vestibular involvement |

| Is the patient dizzy? | If yes, the patient is at risk |

| Degree of hearing loss | Severe to profound |

| Onset of hearing loss | Acquired or progressive |

| Gross motor function | Parents express concern |

| Age-to-sit | Later than 7.25 months |

| Age-to-walk | Later than 14.5 months |

| Single leg stance | Less than 4 seconds (in patients that are seven or older) |

| Bedside head impulse test | Corrective saccades present |

Table 1: Red flags for pediatric vestibular involvement.

References

[1] van de Berg, R., Widdershoven, J., Bisdorff, A., Evers, S., Wiener-Vacher, S., Cushing, S. L., Mack, K. J., Kim, J. S., Jahn, K., Strupp, M., & Lempert, T. (2021). Vestibular Migraine of Childhood and Recurrent Vertigo of Childhood: Diagnostic criteria Consensus document of the Committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society and the International Headache Society. Journal of vestibular research : equilibrium & orientation, 31(1), 1–9.

[2] Verbecque, E., Marijnissen, T., De Belder, N., Van Rompaey, V., Boudewyns, A., Van de Heyning, P., Vereeck, L., & Hallemans, A. (2017). Vestibular (dys)function in children with sensorineural hearing loss: a systematic review. International journal of audiology, 56(6), 361–381.

[3] O'Reilly, R. C., Morlet, T., Nicholas, B. D., Josephson, G., Horlbeck, D., Lundy, L., & Mercado, A. (2010). Prevalence of vestibular and balance disorders in children. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology, 31(9), 1441–1444.

[4] Janky, K. L., Thomas, M. L. A., High, R. R., Schmid, K. K., & Ogun, O. A. (2018). Predictive Factors for Vestibular Loss in Children With Hearing Loss. American journal of audiology, 27(1), 137–146.

[5] Martens, S., Dhooge, I., Dhondt, C., Vanaudenaerde, S., Sucaet, M., Van Hoecke, H., De Leenheer, E., Rombaut, L., Boudewyns, A., Desloovere, C., Vinck, A. S., de Varebeke, S. J., Verschueren, D., Verstreken, M., Foulon, I., Staelens, C., De Valck, C., Calcoen, R., Lemkens, N., Öz, O., … Maes, L. (2022). Three Years of Vestibular Infant Screening in Infants With Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Pediatrics, 150(1), e2021055340.

[6] de Onis, M., Garza, C., Victora, C. G., Onyango, A. W., Frongillo, E. A., & Martines, J. (2004). The WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study: planning, study design, and methodology. Food and nutrition bulletin, 25(1 Suppl), S15–S26.

[7] Janky, K. L., Thomas, M., Patterson, J., & Givens, D. (2022). Using Functional Outcomes to Predict Vestibular Loss in Children. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology, 43(3), 352–358.

[8] Oyewumi, M., Wolter, N. E., Heon, E., Gordon, K. A., Papsin, B. C., & Cushing, S. L. (2016). Using Balance Function to Screen for Vestibular Impairment in Children With Sensorineural Hearing Loss and Cochlear Implants. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology, 37(7), 926–932.

[9] Christy, J. B., Payne, J., Azuero, A., & Formby, C. (2014). Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests of vestibular function for children. Pediatric physical therapy : the official publication of the Section on Pediatrics of the American Physical Therapy Association, 26(2), 180–189.

[10] Perez, N., & Rama-Lopez, J. (2003). Head-impulse and caloric tests in patients with dizziness. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology, 24(6), 913–917.

Presenter

Get priority access to training

Sign up to the Interacoustics Academy newsletter to be the first to hear about our latest updates and get priority access to our online events.

By signing up, I accept to receive newsletter e-mails from Interacoustics. I can withdraw my consent at any time by using the ‘unsubscribe’-function included in each e-mail.

Click here and read our privacy notice, if you want to know more about how we treat and protect your personal data.