Subscribe to the Interacoustics Academy newsletter for updates and priority access to online events

Training in Caloric test

-

Why Perform Bithermal Caloric Testing?

-

Course: Which test, when: Exploring optimal vestibular assessment protocol through illustrative case studies

-

Getting started: VNG

-

Caloric Test vs vHIT: Which One to Use and When do I Need Both?

-

BSA Guidance for Caloric Testing (2010)

-

Course: Caloric Test for Beginners

-

Course: Advances in Videonystagmography (VNG)

-

What is Bilateral Caloric Weakness?

-

Caloric Test vs Rotational Chair vs vHIT

-

Caloric Test: Testing and Analysis

-

Performing caloric testing (VNG)

-

Caloric Test: A Deep Dive

-

Effectuer des tests caloriques (VNG)

-

Le test calorique : une plongée en profondeur

Is Mono-Thermal Warm Screening Enough?

Description

The mono-thermal (“screening”) version of the caloric test refers to stimulating at one temperature on each ear. In many cases the results from two irrigations will be sufficient to inform the tester without the need for all four irrigations associated with the alternating binaural bithermal (ABB) test. This is useful both for saving time and sparing the patient as much discomfort as possible (Adams et al 2016).

With the mono-thermal screen when the interaural asymmetry falls below a certain minimum value (with the overall response size above a certain value amongst other criteria) it is statistically unlikely that two further irrigations will alter the conclusion (the “screen” has returned a “pass” outcome).

However if asymmetry results fall above a certain value (in addition to other criteria), the “screen” has returned a “refer” outcome i.e. four irrigations are needed to fully characterise the vestibular status. The two existing results are used with the two additional results to provide a calculation of caloric weakness and directional preponderance within the same session; i.e. the results of screening are not gathered separately to the ABB test.

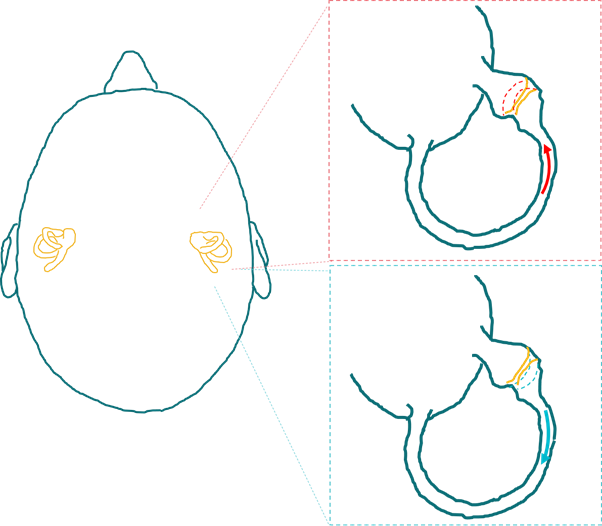

There has been interest in the possible order effects in the bithermal caloric (e.g. Lightfoot, 2004) as well as the use of cool or warm stimuli as part of the mono-thermal screening process. The rationale generally given for using the warm stimulus instead of the cool is as follows: firstly we must consider the possibility of a spontaneous nystagmus produced by a unilateral caloric weakness. Both cool and warm stimuli should reveal this scenario. However, if the unilateral weakness was also accompanied by directional preponderance (often associated with a spontaneous nystagmus) then the directional preponderance will be expected to interact with the caloric nystagmus either constructively or destructively. Secondly we must consider that the warm stimulus has an excitatory effect whereas the cool stimulus has an inhibitory effect. That is, the warm stimulus causes utriculo-petal deflection of the cupula in the horizontal semi-circular canal, which leads to an increase in neural firing in the associated vestibular nerve. The cool stimulus draws the cupula in the opposite direction and leads to a decrease in neural firing on the associated vestibular nerve.

The relevance of this is that a combination of caloric weakness in one direction and directional preponderance in the opposite direction can interact to produce similar sized responses with monothermal cool stimuli (indicating no apparent asymmetry when one does exists). The reason is that a cool (inhibitory) response may not overcome the interaction effects of the directional preponderance on the caloric induced nystagmus. However, this is less likely to occur with warm (excitatory) stimuli. [On the contrary, it should enhance the asymmetry.] In terminology used for describing test performance, the cool stimuli are more likely to lead to a false negative. Minimising such false negatives is a priority, but in so doing, one would inevitably increase the number of false positives. The specificity of the cool test would therefore become lower (than the warm), reducing the benefit in terms of timesaving and minimising patient discomfort.

Lightfoot et al (2009) report that in practice around half of patients are spared the ABB test when using monothermal warm stimuli, whereas only around one quarter of patients are spared using the cool stimuli (higher false positive rate).

Related course

References

Adams, M., et al (2016) Monothermal Caloric Screening Test Accuracy A Systematic Review. Otolaryngology– Head and Neck Surgery 154(6) 982–996

Lightfoot, G (2004). The origin of order effects in the results of the bi-thermal caloric test. Int J Audiol; 43:276-282.

Lightfoot G., et al (2009). The derivation of optimum criteria for use in the monothermal caloric screening test. Ear Hear;30:54-62.

Presenter

Get priority access to training

Sign up to the Interacoustics Academy newsletter to be the first to hear about our latest updates and get priority access to our online events.

By signing up, I accept to receive newsletter e-mails from Interacoustics. I can withdraw my consent at any time by using the ‘unsubscribe’-function included in each e-mail.

Click here and read our privacy notice, if you want to know more about how we treat and protect your personal data.